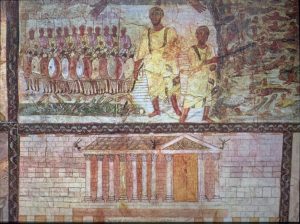

Social and Religious Life in Diaspora (332 BCE-7th century CE)

Dura-Europos – https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AHSC_ORPHANS_1071314236, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=124606350

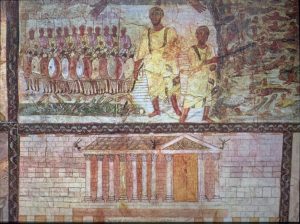

Political, Social, and Economic Developments

Dura-Europos – https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/AHSC_ORPHANS_1071314236, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=124606350

The survival of the Jews and Judaism as a distinct entity in the Greco-Roman world, and, for that matter in every other time and place, depended on the organization of Jewish communal structures. With the exception of a few who were so Hellenized that they disassociated themselves from their coreligionists, virtually all Diaspora Jews were members of the Jewish communal organization, termed in Greek either politeuma (“political body,” “citizens”), katoikia (the designation for a separate settlement or body of residents within a city), or synagoge (“community”). The Jews were organized into autonomous bodies of this kind because they were seen as foreigners born abroad. Other ethnic groups in the Hellenistic world were similarly organized either as foreign ethnic communities or as religious corporations. All such organizations required royal permits and, in the case of the Jewish community, were guaranteed the right to conduct their affairs in accord with their ancestral laws. Thus, the Jewish communities had complete freedom to build synagogues, set up independent courts of justice and other institutions, educate their youth in the tradition, and elect their own officials.

Various officials are known to have existed in the Jewish communities. The archons, from the Greek for “chief, head,” were the members of the Gerousia. The head of the Gerousia was the gerousiarch. There were also the archisynagogos, or head of the synagogue (i.e., the Jewish community, not the house of worship), and various other officials. The synagogue, or temple, was the central building, providing facilities for the instruction of children, the dispensing of justice, and the lodging of visitors, and, of course, serving as the house of worship. Throughout the Diaspora the synagogue became the major institution for the preservation of the Jewish tradition, a role it would soon come to occupy even in the Land of Israel with the destruction of the Temple. Because Jews tended to live in proximity to the synagogue, and would not eat or intermarry with non-Jews, anti-Semites often accused them of exclusivity. From later sources it seems that Jews were not granted equal rights as citizens of the Greek cities, except for small numbers who were considerably Hellenized and were admitted to citizenship as individuals.

In the Hellenistic and Roman eras Jews constituted distinct communities within the larger society. Foremost among their particular needs was exemption from the requirement to worship the local deities, which usually constituted the formal cult of the city. This was usually forthcoming, but it had to be granted informally and is never directly mentioned even in the many documents relating the privileges of the Jews in this period. This unspoken privilege seems to have had the effect of restricting the entry of Jews into full citizenship in most Greek cities.

Yet numerous other privileges are documented. The Jews were permitted to live according to their ancestral laws. Sabbath observance was made possible by excusing them from appearing in court or in municipal offices on the seventh day. Further, Jewish military units were exempted from marching on the Sabbath. Despite the strong resentment of their non-Jewish neighbors, Jews were permitted to send money to the Jerusalem Temple, and later to the patriarchate in the Land of Israel These seemingly minor privileges amounted to a recognition that Jews could live in the Greco-Roman world only at some distance from their neighbors. At the same time, this bit of tolerance made possible their entry further and further into Hellenistic life, and may have sown the seeds for the eventual assimilation of the Hellenistic Jews and the disappearance of Hellenistic Judaism.

The Jews of the Western Diaspora engaged in manifold occupations. They originally came to Egypt, Cyrene, and Asia Minor as soldiers, a role Jews played in many parts of the Hellenistic world. They were generally assigned land which eventually became their private property, thus creating a class of Jewish small farmers throughout the region. Some Jews leased royal lands, while others worked as tenants for large landholders. Agriculture had been important in Palestine, so it is not surprising that Jews continued to be farmers in the Diaspora.

The various literary sources lead us to believe that Jews practiced a wide range of crafts, and that Jewish craftsmen were organized into guilds. There was a large middle class, made up of Jewish traders, including some who owned their own ships and others who were involved in investment. A few Jews amassed tremendous wealth and lent money on interest. Under the Ptolemies Jews occupied government posts in Egypt, including tax collecting. All in all, Jews reflected the occupational distributions of the societies in which they lived and cannot be said to have attained the role of “economic catalyst” to which the Middle Ages, with its restrictions on Jewish occupations, would bring them.

Religious Life

Only a few Jews in the Hellenistic Diaspora went so far as to apostasize from Judaism. A somewhat larger group seems to have become involved in syncretism, identifying the God of Israel with the chief pagan deity, a phenomenon which had grievous consequences in Judea. Some scholars have mistakenly considered the religion of the syncretists to have been the dominant Judaism of the Diaspora, but in fact this approach had few adherents, and for the most part, the Diaspora Jews were loyal to their ancestral ways and faith. At the same time, however, they eagerly sought to adapt and accommodate to the surroundings in which they lived, especially when they came to have the same educational background and occupations as their neighbors, a process that was abetted by the many shared ethical concepts of Judaism and the Greek philosophical tradition.

The writings of numerous Greek and Latin authors testify that the Jews of the Greco- Roman world observed such central commandments as the Sabbath, the laws regarding forbidden foods, and circumcision. The influence of the synagogues on many Greco- Roman pagans leads us to believe that they were well attended. Here Jews gathered to worship and to hear homilies which taught them how to synthesize Judaism with the prevailing culture. Synagogues were found throughout the Diaspora, often more than one in a community. Some were magnificent structures which were part of the complex of public buildings of their respective cities.

We cannot be certain of the language of prayer in Hellenistic synagogues. In all probability, at least the greatest part of the worship service was conducted inkoine Greek, the dialect of the Hellenistic world. Evidence points to the use of psalms as part of the service, clearly in imitation of the Temple ritual. As for the reading of the Torah, it is virtually certain that Greek Bible texts, of which the Septuagint is an example, were in use. It is not known for sure, though, whether the formal Torah reading was conducted in Greek or took place from the Hebrew text with the Greek, much like the later Aramaic targums, serving as a translation. Tombstones indicate that Diaspora Jews had at least some knowledge of Hebrew. Moreover, a process of Hebraization can be observed in the later Roman and Byzantine periods as Hellenistic Judaism was pulled in two contradictory directions, toward Palestinian tannaitic Judaism on the one hand, and toward assimilation to the Christianized Roman world on the other.

Jews in the Greco-Roman world celebrated the Sabbath, as well as the annual cycle of festivals and new moons, just as did their brethren in Palestine. They gathered for festive communal meals and erected booths for the festival of Sukkot. Some communities observed local commemorative days as well. Strong ties to the Land of Israel were maintained. In the years before the destruction of the Temple, Jews from great distances streamed to the holy city for the pilgrimage festivals. Various Temple furnishings were donated by Diaspora Jews. Regular Temple taxes were collected throughout the Diaspora and sent to Palestine. After the destruction of the Temple, Diaspora communities continued to support the patriarchate in Palestine.

Nevertheless, some scholars have argued that an attenuation of ritual observance did occur in the Hellenistic world. A more serious threat to traditional Judaism came from philosophically oriented Jews who explained the Torah as an allegory and therefore maintained that the commandments did not have to be observed. Philo Judaeus, the Alexandrian, forcefully objected to this approach.

All in all, the Judaism of the Greco-Roman Diaspora set patterns of communal organization that would carry Jews through the next two thousand years. The collapse of Hellenistic culture and the rise of Christianity ultimately led to its decline. Yet in its heyday Hellenistic Judaism was vibrant and committed; its strength is best demonstrated by the many semi-proselytes who flocked to its institutions and by the rich literature it left.

Excerpted from Lawrence H. Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991.

Overview

Articles

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website