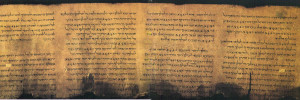

Harmonic and Mystical Characteristics in Poetic and Liturgical Writings From Qumran, Bilhah Nitzan, The Jewish Quarterly Review 85,1-2 (1995).

Basic to Jewish thought is the existential separation between God and nature, and hence between God and man- “The heavens belong to the Lord, but the earth he gave over to man” (Ps 115-16). Nevertheless, both biblical and post-biblical literature express the desire to bridge the existential distance between God and man. The human longing to approach God is expressed by the biblical psalmists in statements of the faith of the pious as they celebrate the grace of God experienced by his people in the temple (Ps 42-43; 73- 17, 23-28; 92-2). On the other hand, the prophetic merkavah speculations of Isaiah 6 and Ezekiel 1, 3, 8, and 10, portray the disparity between God in his heavenly dwelling and the sinful people in their earthly temple; these give voice to the mysterium tremendum felt by man in the presence of God. According to Post-biblical merkavah speculations (as found in the books of Enoch, the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Apocalypse of Isaiah, and the late Hekhalot literature) the pious ascends spiritually to heaven seeking to approach God. During such a transcendent experience the individual is cut off from earthly feelings, and focuses mystically on the longing to be close to God. Much later, in eighteenth-century hasidism, such longing is expressed in the context of quietistic experiences. Thus, expression of the human desire to bridge the existential distance between man and God is subject to historical and conceptual varia¬tions and cannot be

defined in a uniform manner.

Generally speaking, the transition from the experience of feeling the closeness of God on earth to that of seeking him in his heavenly dwelling, or with his heavenly entourage, is related to the religious consciousness of loss of the enlightening, steadfast love of God to his people during times of sin and punishment. Thus, in periods of crisis such as those following the destruction of the First and Second Temples, and during the long periods of exile, Jewish writers expressed the feeling that God had “hidden his face” from his people. The desire to recapture God’s steadfast love to his people was expressed differently in the writings of various circles of post-biblical Judaism. It found expression both in halakhic activity and in prayer and religious poetry. The following discussion will focus on the latter.

In Qumran poetry one finds clear statements concerning the religious experience of communion between human beings and the celestial entourage; for example, the pious is chosen “to stand in the assembly with the host of the saints and to come into communion with the congregation of the sons of heaven… to praise Your name in the choir [of rejoicings] …” (1QH iii 21-23). However, such statements do not indicate an experience of a spiritual ascent to the heavens. Rather, such passages, which speak of the salvation of the pious from subjugation to sin and impurity caused by the physical nature of man and the sinful character of society, ex¬press an earthly experience. This is neither an ecstatic nor a quietistic experience that cuts off the individual from earthly existential feelings. On the contrary, even though the poet of the Thanksgiving Scroll describes the religious experience of the individual, he is a member of a human congregation. These men attempted to mend their ways by leaving the society of their time to dwell in their own settlements and camps; they followed their particular interpretation of the scriptural laws and thereby took an active part in the process of renewing the steadfast love of God toward his people. Thus, in cutting themselves off from the evil society, the members of the yahad community reached a consciousness of innocence and purity elevating them to a level similar to that of the angels. They therefore felt that they could sing praises to God like, and together with, the celestial entourage. According to another poetic statement preserved in the Songs of the Maskil (4Q511 35), the praises of God by righteous men who are “purified seven times” is reckoned as tantamount to the service of the angelic priests in the heavenly temple. Such a statement fits with the yahad’s disqualification of the earthly priests for profaning the sanctity of the temple and the holy city. In cutting themselves off from worship in the earthly temple (see 1QS ix 4-5; CD xi 18-24) and in considering themselves to be like pure priests, they claimed that their praise of God resembles that of the angels and is in unison with them. This manner of approaching God may indeed be considered mystic. To clarify this point, I shall describe the characteristics of such praise, whether sung by human beings or by the angelic hosts themselves.

II

I shall discuss the praise of God recited by angels and men in terms of its cosmologic and mystical approaches found in biblical, Qumranic, and rabbinic literature.

Cosmologic Approach. This approach appears in biblical, apocryphal, and Qumran poetry (Ps 89-6-15, 103-19-22, Ps 148, Tob 8-15, Pr Azar 36-67, Hymns on the Sabbath Day [4Q504 1-2 vii 4-9], Hymn to the Creator [11 QPsa xxvi 9-15], 4QBerakhot [4Q286-290]), as well as in apocalyptic descriptions of the eschatological praise of God (l Enoch 61-9-13, 4Q511 1). In these hymns all natural and supernatural beings, earthly and heavenly, are considered as creatures of God, the unique ruler of the universe. All created beings, including the angels, are equal before God. Thus, the praises invoked from all the cosmos express in harmony the magnificence and majesty of God, the creator of the whole universe. The Qumran hymns reflecting this approach include only a few distinctive features, as I shall detail below (see sec. III).

Mystical Approach. This approach includes two different aspects, the celestial approach and the communionist approach.

(1) Celestial Approach. This approach elevates the praises and prayers uttered by the celestial entourage above those recited by the earthly beings. The song uttered by the divine celestial entourage before the Throne of Glory has a special function- to extol the holiness of God and to give expression to the divine glory. This approach is reflected in the Bible in the recitation of the Qedushah by the seraphim in the vision of Isa 6- 1-3 and in the blessing of the divine glory elevated by the chariot in Ezek 3-12. In the pseudepigraphic literature it appears in the exclusive attribution of the recital of “Holy” and “Blessed,” per Isa 6-3 and Ezek 3- 12, to those angels who stand before the divine glory (1 Enoch 39- 12-¬13, Adam and Eve 37-1-3, 43-6). This approach is likewise reflected in the description of the prayers uttered by the angels on behalf of those who dwell in the land (l Enoch 39-5, 40-6,47-1-2), as well as in the description of the task imposed upon the chief angels to take the prayers of the righteous “before the glory of the Lord” (Tobit 12- 12, 15). Rabbinic literature describes the ministering angels, who praise God, as “more modest than human beings” and as having a higher ethical level (Aboth de Rabbi Nathan A 12, [ed. Schechter, p. 51], etc.) In Qumran literature this approach appears only in the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice, and will be discussed below (see sec. IV).

(2) Communionist Approach. This approach acknowledges the possibility that those human beings who are righteous and free of transgression (in other words, people who are cut off from the sinful nature of human beings) may recite praises in company with the angels and thus attain a spiritual experience of communion with the celestial entourage. This motif is clearly expressed in the apocalyptic literature (l Enoch 39-7, 61-12), and even more so in Qumran (see 1QH Hi 21-23, 4Q511 35 etc.) and in later Hekhalot literature.

It is only after the destruction of the Second Temple that we find a talmudic midrash to Ps 42-9 that describes “bands of ministering angels who recite praise at night and are silent by day, in deference to Israel” (bHag. 12b). However, this is somewhat different from what we have found in Qumran, as it evidently refers to the supplicatory poems of the people of Israel rather than to praise of God for its own sake recited by the angels. Moreover, whereas in 1 Enoch 40-6 supplication for the sake of the people is recited by one of the angels of the inner sanctuary, in the Hekhalot literature one finds that an extremely righteous man “who descends to the merkavah” has earned the right to ascend to the level of the angels who extol God before his holy throne, and is allowed to recite Qedushah in the celestial heights and to stand before the holy throne with the angels when God considers Israel’s supplications. There is no such descent to the merkavah in the Qumran writings, nor recitation of the Qedushah before the heavenly throne and among the earthly worshippers. However, an experience of harmony and communion between the chosen earthly and heavenly worshippers is reached through hymns recited by his pure and perfect worshippers.

III

Does the idea of harmony and communion apply equally or differently to the relationships between man and God and to the relationships between the created beings of heaven and earth? According to the Jewish monotheistic faith, the idea of the transcendent God cannot be reached through observation of created beings. Therefore, in both biblical and post-biblical literature, the idea of the Glory of God is expressed by means of heavenly voices or by speculations concerning the appearance of the Glory of God upon his throne, his radiance, his garments, his names, as well as his angelic entourage. Nevertheless, when dealing with the praise of God, both men and angels are considered as created beings who worship God in harmony and communion.

As for the literary aspect, how is the experience of harmony and communion expressed through hymns of praise? There are two different types of poetry of praise- descriptive hymns and liturgical hymns of praise.

Descriptive cosmological poetry, such as Pss 8, 19, 104, ex¬presses the harmony of all created beings through wonderful descriptions of their relationship with one another according to the wisdom of their creation; and in this way express praise of the Creator. The descriptive hymns of lQH i; xiii; and the earthly and astronomical descriptions in 1 Enoch 2- 1-5-2; 41; 43-44; and 72-82 express the harmony of the entire creation by showing the dominion of the heavenly realms over the earthly realms, as well as the harmony of the astronomical order. Such detailed descriptions, both prosaic and poetical, promote feelings of admiration for the Creator, whose law keeps the whole universe in harmony.

Another kind of religious emotion is aroused by means of liturgy—namely, by the blessing and praising of the Creator invoked from all of the realms of creation. This type of liturgical hymn is found in the biblical psalms such as Ps 103-19-22; 148; and ISO, and in certain hymns from Qumran. For example, in the Hymns on the Sabbath Day (4Q504 1-2 vii 4-9), all created beings of the heavenly and earthly realms, and even the realm of “the great [abyss] and abaddon,” are summoned to bless God on the Sabbath day. Although the hymn is structured as a summons to a list of worshippers, and the wording of their praise is not specified, it is clear, according to the heading הודות ביום השבת, that all the created realms are in harmony in sanctifying the Sabbath day by praising the Creator. According to 4Q511 1, all created beings will be invited to praise God at the end of days, when all the wicked spirits are destroyed. Although this hymn specifies the reason for the praise, the experience of harmony is achieved by the enumeration of the worshippers in all parts of the universe who will rejoice over the mighty acts of God. Those biblical and apocryphal cosmological hymns which invite all heavenly and earthly creatures to bless and praise God express the ideas of harmony and rejoicing systematically, inviting all the worshippers through the repeated recitation of a particular formula. The impression of harmony is created by the repetition of the same formula as each of the worshippers is summoned. In Ps 103-20-22, ברכו ה’ (“bless God”) is repeated three times; Psalm 150 expresses the means of praising God from heaven to earth through the use of repetitive summonses, such as הללו אל ב- / הללוהו ב-; while Pr Azar 36-67 details a long list of worshippers according to one repetitive formula, ברכו את ה’ … הללוהו ורוממוהו לעולמים. Although these hymns contain no explicit description of the majesty of God, and even though the worshippers of God are separated into distinct realms of heaven and of earth, the uniform recitation of the praise by all creates the experience of harmony. This harmony is explicitly ex¬pressed in the closing statements of the hymns, such as כל הנשמה תהלל יה (Ps 150-6); ברכו ה’ כל מעשיו בכל מקומות ממשלתו (Ps 103-22). Thus, the experience of harmony is achieved in the liturgical hymns by (1) the repetition of calls to praise, rather than the words of praise per se; (2) the wholeness of the praise recited throughout the universe; (3) the liturgical repetition of a specific formula throughout the universe. These qualities appear as well in the cosmological blessings of 4QBerakhota,b (4QBera,b), albeit freely formulated, and in systematic and more complicated formulae in the angelic liturgy of the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice.

The blessings to God preserved in 4QBera (4Q286) and in 4QBerb (4Q287) consist of liturgical blessings to God by both the heavenly realms and the earthly realms of his kingdom. The blessings are structured not according to the words of the heavenly and earthly worshippers, but with lists describing the worshippers and their blessings. The extant blessings in both manuscripts open with phrases of praise related to biblical and pseudepigraphic merkavah visions, such as-

מושב יקרכה והדומי רגלי כבודכה

ב[מ]רומי עומדכה ומדר[ך] קודשכה

ומרכבות כבודכה כרוביהמה ואופניהמה וכול סודי [המה]

מוסדי אש ושביבי נוגה וזהרי הוד נה[ור]י אורים ומאורי פלא

The seat of your glory and the footstools of your honor in the

[h]eights of your standing and the trea[d] of your holiness;

and the chariots of your glory, their cherubim and their ophanim

(wheels), with all [their] councils;

[foun]dations of fire and flames of light, and flashes of splendor,

ri[ver]s of flames, and wondrous lightnings.

(4QBerb lab ii 1-3)

כיוריהמה […ת] בניות הדרמה…

[קירות אול] מי כבודמה לדתות פלאיהמה…

[…] מלאכי אש ורוחי ענן…

[זו]הר רוקמת רוחי קודש קוד[שים…

Their engraved forms […], their splendor [i]mages,…

[walls of] their glorious [hal]ls, their wondrous doors, …

[…] angels of fire and spirits of cloud, [….],

[bri]ghtness of the mingled spirits of the holiest ho

[liness…].

(4QBerb 2ab 1-5)

These phrases are related to the merkavah visions both in content and their numinous terms and style. However, in their context in 4QBerakhot, most of these phrases are not intended to describe the heavenly temple and the heavenly entourage, but primarily to list the heavenly worshippers of the divine glory. That is apparent in 4QBera and in 4QBerb, both of which describe the blessings to God in a parallel order, opening with blessings of the heavenly realms, including those of the angelic hosts, followed by blessings of the earthly realms. Thus, the blessings of 4QBerakhot are primarily structured as lists of worshippers.

Each of the lists of the heavenly worshippers is distinguished by a different use of the preposition ב. For example, the list of the mighty angels in 4QBera indicates the manner of praise of these angels, using the preposition ב adverbially, as follows-

[…]ם בעוז הדרמה

וכול [ר]וחי משאי מקד[ש…]

[…] בסוד [יהמה ובמ] משלותמה

גבורי אלים בכח

[…] קנאת משפט בעוז

[…] …with their splendor might;

and all [s]pirits of the sanctu[m] who uplift (the praise)

[…] at [their] councils [and r]ealms.

Mighty elim in power,

[…] zeal for judgment with might.

(4QBera 2ab 1-3)

But the list of the angelic ministers of the heavenly temple in 4QBerb 2ab 9-3 I uses the preposition ב to indicate their qualities, their place of serving, their appearance, and their acting, as follows-

וכול משרתי ק[ודש…]

[…] בתמים מעשיה[מה]

[…]ש בהיכלי מ[לכותכה]

[……….]

כול משרת[יכה בתפארת] הדרמה

מלאכי […]

[רוחי] קודשכה במעו[ני פלאיהמה

מ]לאכי צדקכה [בהפלא נור] אותמה

And all the ministers of ho[liness …]

[…] in the integrity of th[eir] works;

[…]…in the temples of [your] k[ingdom]

[…]

all [your] ministers [in their beauty] splendor,

angels of […],

[spirits] of your holiness in their [wondrous]

habita[tions],

[a]ngels of your righteousness [with] their [marvelous pro]digies.

(4QBerb 2ab 9-3 1)

Such literary techniques for using the preposition ב are probably reflective of the style of Psalm 150, and likewise of 1 Enoch 61-11 (see below). Thus, we might recognize here a traditional style of cosmological and heavenly liturgy.

However, the lists of earthly worshippers are distinguished from those of the heavenly worshippers by other means, such as a simple list which details the creatures of flesh- [ב]המות ועוף ורמש ודג [י]מים, “[ca]ttle and birds, and creeping things, and fish of the [s]eas” (4QBerb 3 3), or by another style used in the list of the earthly creatures in 4QBera, as follows-

הארץ וכול [א]שר [עליה

תבל וכול] יושבי בה

אדמה וכול מחשביה {י}

[ארץ וכו]ל יקומה

[הרים וכו] גבע[ו]ת

גיאות וכול אפיקים

ארץ ציי[ה…]

…

עצי רום וכול ארזי לבנ[ון]

[…]

The earth and all [t]hat is [on it,

world and all] its inhabitants;

ground and all its depths,

[earth and al]l its living things;

[mountains and al]l hil[l]s,

valleys and all ravines, desola[te] land […]

…

lofty trees and all the cedars of leban[on], […]

(4QBera 5ab)

Nevertheless, the differing styles used to identify the cosmological worshippers who bless God do not disturb the impression of the harmony of all heavenly and earthly worshippers. On the contrary, all of the created beings in the heavenly and earthly realms are unified and harmonized in blessing God. This idea of harmony is expressed by similar liturgical phrases used to open or close the lists of all the heavenly and earthly blessings in 4QBerakhot. Phrases such as [יברכו בי]חד כולמה את שם קודשכה (4QBera 2 4), [יברכו] את שם כבוד אלוהותכ[ה] (4QBerb 2ab 8), and ויברכו את שם קודשכה בברכות (4QBerb 3 1) indicate the blessings of the heavenly realms; and phrases such as [ויב]רכוכה כול בריאות הבשר כולמה אשר ברא[תה] (4QBerb 3 2) and [ויברכ]וכה ביח[ד] כולמה. אמן א[מן] (4QBerb 5 5) indicate the blessing of the earthly realms. The terms כולמה and ביחד, which describe the blessings of both the heavenly and the earthly realms, express the harmony and unison of their blessing of the glorious name of God.

Moreover, a list of the liturgically appointed times for blessing God (4QBera 1ab ii 9-11), as well as phrases such as בחדשים שנ[י עשר], “in twe[lve] months” (4QBera 5ab 7), בכול מועדי, “in all the due times” (4QBerb 1 3), and בקצי מ[ועד], “in times appointed to be fe[stivals]” (4QBera 7 i 4), etc. indicate that all created beings of heaven and earth who bless God in the appointed times are united in keeping his ordinances; see the phrase [לשמור/לקיים] את דברכה אמן אמן (4QBera 5ab 8).

Despite the cosmological approach, which creates the impression of harmony by considering equally all the creatures of the universe, one may not ignore the two groups of worshippers which are mentioned separately, as stated in 4QBera 7 i 2-7-

[וכו]ל בחיריה [מ]ה […] וכול ידעיהמה

בתהלי […] וברכות אמת בקצי מ[ועד]

………..

[ס]וד אלי טוהר עם כול ידעי עולמים

להל[ל ולבר]ך את שם כבודכה בכול [קצי עו]ל[מים].

אמן. אמן

[and al[l their elect […] and all their learned (men)

with psalms of […] and blessings of the truth in the times

appointed to be fe[stivals];

…

[the c]ouncil of elim of purification with all those who have

knowledge of eternal things

for prai[sing and bles]sing your glorious name in all

[ever]la[sting ages].

Amen. Amen.

According to this passage, the chosen people, together with the angels who have a specific insight (possibly that of the mysteries of the liturgical appointed times for blessing God ברכות אמת בקצי מ[ועד]), bless in unison. As the complete list of the other worshippers is structured in a descending order, one cannot see here the gradual mystical elevation from the lower stages to the highest level of those dwelling close to God, as known from several merkavah speculations. Nevertheless, the specific status of the chosen creatures of heaven and earth above all other creatures may be considered mystical in two respects- in their superiority above all other worshippers, and in their communion. Thus, one may suggest that the text of 4QBerakhot reaches a mystical height in its climax. The parallel description of both the heavenly and earthly chosen worshippers appears to bind those who know and keep the law of praising God in the appointed times, thus bridging the distance between heaven and earth.

To summarize thus far- whereas the biblical cosmological hymns contain no information concerning the appointed times for blessing, the liturgical hymns from Qumran are recited at specific appointed times and ceremonies; namely, on the Sabbath (4Q504 1-2 vii 4-9), on the occasion of magical ceremony (4Q511 1), and possibly at a ceremony concerning the covenant with God, perhaps on the Day of Pentecost (4QBerakhot). Thus, the lists of those who bless God during the ordained appointed times are in¬tended to demonstrate the authority of the precepts of God in harmonizing all of the heavenly and earthly created beings who act according to this law. In other words, such hymns confirm that the law which harmonized the whole created world is the only correct law of God.

IV

An angelic liturgy, consisting of thirteen songs, appears in the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice, preserved in nine manuscripts in Qumran and in one manuscript in Masadah. These songs were intended for cultic use during thirteen successive sabbaths of one periodic cycle, or possibly for each of the four parallel periodic cycles of the year, according to the 364-day calendar. The songs describe the liturgy of the classes of the heavenly hosts and priest¬hood, in ascending order- from the classes of the lower degree to the high angelic priesthood. Most of the songs are descriptions of the heavenly worshippers, their graduated order, and the liturgical system of the praises they utter. They constitute the most detailed expression of angelic liturgy extant in ancient Jewish literature.

Neither the Qedushah of Isa 6-3 nor the blessing of Ezek 3-12, which are the main blessings recited by the angels in biblical and post-biblical hymns, are recited in these Sabbath songs. This is noteworthy, even though most of the songs do not detail the wording of the angelic praises but only their subject matters, as the attribute of holiness is considered but one of the subject matters of the praises. However, as we shall see below, the mode of the recital of the Qedushah and the “Blessed” appears in other praises, and is even used to reach the highest degree of exaltation of God.

Despite the absence of the Qedushah recitation itself, the descriptions of the heavenly sanctuaries, the chariots, the Throne of Glory, and the angelic hosts may be considered as mystical. They are described in sublime and numinous wording and style, related mostly to the merkavah vision of Ezekiel, thereby reflecting the mysterious exalted atmosphere of the heavenly kingdom of God. Note, for example, the following phrases from the song of the twelfth Sabbath-

יפולו לפני הכרובים… והמון רנה ברום כנפיהם, קול [דממ]ת אלוהים,

תבנית כסא מרכבה… כמראי אש רוחות קודש קודשים סביב…

ומעשי נוגה ברוקמת כבוד

…

The cherubim fall before him and bless… and there is a tumult of jubilation as their wings lift up, the sound of divine [stillnes]s. The image of the chariot throne…. Like the appearance of fire (are) the most holy spirits round about…. And there is a radiant substance with glorious colors…

(4Q405 20-22 ii 7-11, etc.).

Even though this description is not a mystical vision per se but an interpretation of Ezekiel’s vision, a serene and sublime atmosphere is created by such numinous terms and style.

Others might consider as mystical, or even magical, the use of the typological number seven in the Sabbath songs in various forms, such as- the sevenfold organization of the angelic priests, indicating the existence of seven holy areas, such as seven devirim of the heavenly temple (Newsom, Songs, p. 31); structures of sevenfold liturgical formulae, which are sometimes tripled; and the centrality of the seventh Sabbath. The typological repetition of sevenfold praises characterizes angelic liturgy in the Bible (Ps 29, 148-1-4) and in 1 Enoch 61- 11-12. Likewise, threefold praises characterize such biblical angelic hymns as Ps 29-1-2a and 103-20-22, and the Qedushah of Isa 6-3 and its post-biblical liturgical recitals.

In any event, a comprehensive study of the Sabbath songs demonstrates that both the numinous descriptions and the sevenfold repetition are focused upon the liturgical function of the heavenly cult of the Sabbath. Phrases concerning the praise of God appear from the song of the first Sabbath to the thirteenth as follows- all the songs open with a summons to praise God, such as הללו לאלוהי and the like, while the liturgy of praise is performed not only by the angelic choirs, but by all the heavenly sanctuaries. The songs for the first two Sabbaths concentrate on the description of the heavenly priesthoods and their liturgical function, such as-

He established for himself priests of the inner sanctum, the holiest of holy ones… priests of the lofty heavens who [draw] near… [pr]aises of [your] lofty kingdom

(4Q400 1 i 19-ii 1)

[. . .] to praise your glory wondrously… and the praiseworthiness of your royal power… the glory of the King of godlike beings do they declare.

(4Q400 2 1-5)

From the song of the fourth Sabbath on, there are vestiges of the liturgical songs themselves (4Q401 3 etc.) or of some descriptions of the songs, such as יהלל שבעה (4Q401 13 2), להלל כבודכה פלא (4Q401 14 i 7), קול רנות (4Q401 14 ii 3), [י]שמיעו בדמ[מת] (4Q401 162, 4Q4029 2), etc. Systematic sevenfold liturgies and other phrases relating to the manner of praise manifest a gradual ascent, both in the degree of the angelic worshippers and in the manner of their praising.

The songs of the sixth and the eighth Sabbaths are to be per¬formed by several choirs of seven chief princes of the angelic hosts (the sixth Sabbath) and of seven chief princes of the angelic priest¬hoods (eighth Sabbath). However, in these songs there appear not the songs of praise recited by the angelic princes, but instructions concerning the liturgical process of their praise, formulated in specific formulae. According to these instructions, the very act of recitation is to proclaim the praise of the attributes of God, or the blessings conveyed to the worshippers in the name of God according to his attributes- one after the other, in successive turn, from the first to the seventh chief prince. Only the conclusion of these songs is to be recited together by all the angelic chief princes (4Q403 1 i 26-28, 4Q404 4 6-7). Thus, by gradually giving the right of praising from the first to the seven chief prince in each choir, and by the recitation of a conclusive blessing to God by all seven chief princes of each choir, a gradual elevation of the praise is achieved. Moreover, the song of the seventh Sabbath is recited not by seven chief princes, but by choirs including all the angels of seven angelic hosts. The song of the eighth Sabbath is to be performed by a higher degree of angelic worshippers—namely, by the seven chief princes of the heavenly priesthoods. The gradual elevation of the praise is also accomplished in this song by means of increasing sevenfold the praise sung by each of the angelic worshippers, through its liturgical transition from the first to the seventh chief princes (4Q403 1 ii 27-30; 4Q405 11 2-5).

The mode of recital in these songs is similar to that of the recital of the Qedushah and the “Blessed” as known from the traditional interpretation of their recital. According to the Aramaic translation of Pseudo-Jonathan to Isa 6-3, the phrase וקרא זה אל זה ואמר (“and one called to another and said”) is interpreted- ומקבלין דין מן דין ואמרין (“they receive from one another and say”). In the Sabbath songs from Qumran such a style of recital is acted out by a group, in which the participants give (or receive) from one another the right to utter praises.

The gradual transition to the praises of the chariots and the cherubim of the heavenly throne is accomplished by the description of the praise recited by the heavenly sanctuaries. The opening statement refers here not to the angels but to heavenly structures-

With these let all the f[oundations of the hol]y of the holies praise, the uplifting pillars of the supremely lofty abode, and all the corners of its structure.

(The Seventh Sabbath, 4Q403 1 i 41)

Even though this opening is followed by detailed descriptions of the sanctuaries themselves and their angelic hosts, one finds to¬ward the closing-

And all the crafted furnishings of the devir hasten (to join) with wondrous psalms… devir to devir with sound of holy multitudes.

(4Q403 1 ii 13-14)

The song ends with the description of their praise, which bears a certain similarity to the closing of the praises and blessings of the angelic hosts in the sixth Sabbath-

And the chariots of his devir give praise together, and their cherubim and thei[r] ophanim bless wondrously.

(4Q403 1 ii 15-16)

Moreover, the liturgical system of the praise of the devirim, דביר לדביר בקול המוני קודש (“devir to devir in the sound of holy multitudes” [4Q403 1 ii 14]), follows another interpretation of the man¬ner of recitation of the Qedushah of Isa 6-3 and of the blessing of Ezek 3- 12-13. According to this approach, the biblical description, “and one called to another and said…” (וקרא זה אל זה ואמר, Isa 6-3), and the vivid imagery of Ezekiel, “it was the sound of the holy creatures brushing against one another, and the sound of the wheels beside them” (וקול כנפי החיות משיקות אשה אל אחותה וקול האופנים לעומתם, 3- 13), are interpreted as the song of an antiphonal choir of two voices. This manner, which has become the model for recitations by two groups of angels in post-biblical literature, is performed here in the praise of the sanctuaries. The relating of such a manner of praise to the heavenly sanctuaries, such as the devirim in the Sabbath songs, was perhaps intended not only to express the fullness of the liturgical praising of God all around the heavenly realms, but also to specify the type of praise that was performed in the devirim, the most holy place among the heavenly sanctuaries with the exception of the Throne of Glory itself. However, the praise of the angelic camps who serve before the Throne of Glory is described in the twelfth Sabbath song according to the other style of the recital of the Qedushah, mentioned above- “all their mustered troops rejoice, each o[n]e in [his] stat[ion],” [י]רננו כול פקודיהם אחד א[ח]ד במעמד[ו] (4Q405 20 ii-22 6).

It is clear that human beings do not participate in the choirs of the angelic hosts, nor ascend to the heavenly sanctuaries to be close to the angelic choirs. According to the statement preserved in the song of the first Sabbath, the angelic hosts and priesthood are considered the “honored among all the camps of godlike beings and reverenced by mortal councils” (4Q400 2 2); while men who are conscious of their lower level say-

How shall we be considered [among] them? And how shall our priesthood (be considered) in their habitations? And our ho[liness—how can it compare with] their [surpassing holiness]? [What] is the offering of our mortal tongue (compared) with the knowledge of the el[im…]?

(4Q400 2 6-7)

Indeed, the religious experience of the people who wrote or used the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice was not analogous to that of the mystic experience of the later “descenders to the merkavah.” Nevertheless, whether the songs of the angelic liturgy were recited by the earthly worshippers on the correct dates of each Sabbath in their earthly dwelling, or whether these songs only reflected the knowledge of the heavenly mysteries which were revealed to their poets, they may have been considered as a medium for creating an experience of mystic communion between the earthly and the heavenly worshippers, each one of which kept the Sabbath law in their respective dwelling, but with a single, united faith.

To summarize- This paper has examined two types of hymns from Qumran- the cosmological hymns that create an experience of harmony with the entire universe through the performance of God’s law at the appointed times, and the liturgy that creates a mystic experience while symbolizing the acceptance by God of those hymns recited by his pure and perfect worshippers. Both of them were used to demonstrate the concept of the yahad circles concerning the proper worship of God. Thus, in reciting these hymns at their appointed times, the earthly worshippers attained the experience of closeness to God through the correct performance of the law of his worship.

Pages 163-183

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website