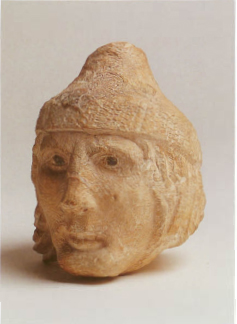

Head of Crusader Knight, 13th century

The Crusaders invested tremendous resources in building projects all over the country, and many of the edifices they built are still standing today. Among the most impressive of these are the great fortresses constructed at strategic points throughout the country. One of these, known as Monfort (which means “strong mountain” in French), was erected by the Knights of the Teutonic Order in 1227 on the foundations of an earlier structure. Its location on steep, narrow ridge in an oak forest overlooking Nahal Keziv lends the site a “European” appearance. The Teutonic knights gradually acquired lands throughout the Galilee, ultimately controlling some fifty settlements. In 1266, the Mamluk sultan Baybars attacked Monfort for the first time, but the tenacious Christian defenders forced him to retreat. Five years later, Baybars’ soldiers managed to break through the fortress and defeat the knights, who were allowed to depart for Acre. The fortress was abandoned, never to be reoccupied again.

The head of a knight discovered at Monfort was made in the realistic style common in French Gothic sculpture. In this case, however, the artist broke with convention and added details that are so individual as to suggest a portrait of an actual person. The head was sculpted in limestone with a chisel, whose marks are still visible. The knight is portrayed wearing a helmet, and his eyes are inlaid with lead. The sculptured head probably decorated the facade of one of the fortress’s buildings.

Ilan, Ornit. Image and Artifact; Treasures of the Rockefeller Museum. Jerusalem- Israel Museum, 2000, p.94.

See also-