Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Lawrence Schiffman, From Text to Tradition, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ, 1991, p.120-138.

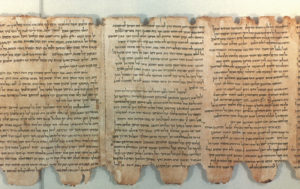

The Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls

In the preceding chapter several of the groups or sects of the Second Commonwealth period were surveyed. These and a variety of other less well known groups left a vast literature which has come down to us in a number of forms and languages. Before investigating the nature and origins of this literature, it will be helpful to begin with a few definitions. The term “apocrypha” refers to those books which are found in the Hellenistic Jewish Bible canon of Alexandria, Egypt, but not in the Palestinian Jewish canon. The Hellenistic canon was preserved by the Christian church in the Septuagint and Vulgate Bibles, and the Palestinian canon was handed down in the form of the traditional Hebrew Bible. “Pseudepigrapha,” strictly speaking, are books ascribed by their authors to others, in this case to ancient and venerable biblical heroes, but the term also designates writings from the Second Temple period, preserved mostly by Eastern churches, in such languages as Greek, Slavonic (a medieval Slavic dialect), Ethiopic, and Syriac. The term “apocalyptic” refers to books which present revelations in a narrative framework in which an otherworldly being discloses mysteries to a human being. These revelations usually concern both eschatological salvation and a supernatural world. The Dead Sea Scrolls are a collection of manuscripts from the caves of Qumran on the western shore of the Dead Sea among which are many writings from this period as well as much material from the Hebrew Bible. Among these scrolls are biblical texts, apocryphal and pseudepigraphal texts, and various sectarian compositions.

THE APOCRYPHA

The apocrypha, as mentioned earlier, consists of a body of texts that form part of the standardized corpus of the Septuagint and other Greek Bibles. Our presentation here will discuss the various genres and books included in it.

The desire to supplement Scripture was part of a general tendency in the Greco-Roman period toward “rewritten Bible.” In such works the authors, out of reverence for the Bible, sought to extend the biblical tradition and often applied it to the issues of their own day. One of the books of this type is 1 Esdras (3 Esdras in Latin and Roman Catholic Bibles). It begins with a description of the great Passover held by Josiah, king of Judah, in Jerusalem in 621 B.C.E. according to 2 Chronicles. It then reproduces an alternative version of the whole of Ezra and parts of Nehemiah, ending in the middle of the account of Ezra’s reforms. The author wanted to emphasize the contributions of Josiah, Zerubbabel, and Ezra to the reform of Israel’s worship. From the confused chronology, it is clear that the author did not have access to superior historical texts. He sought to “correct” the canonical text based on his own analysis, a process in which he was not successful to judge from the remaining inconsistencies. The work appears to have been adapted in Greek from the more literal version in the Septuagint, although some argue for composition in late biblical Hebrew. It is most probable that the book is to be dated to the second half of the second century B.C.E. and assigned to a Hellenistic provenance. Josephus relied heavily on this book.

Tobit is a short didactic story. It is set in Nineveh in Assyria after the exile of 722 B.C.E. Tobit son of Tobiel, a righteous man who has become blind, sends his son Tobias to Media to seek some money belonging to him. Tobias is guided by the angel Raphael. In Media, with the angel’s help, he weds Sarah, whose previous seven husbands had died on their wedding nights at the hand of the demon Asmodeus. The couple returns home to Nineveh, where, again with the angel’s help, Tobias cures his father’s blindness. As the names show (tov = “good”), the book points out the rewards for ritual and ethical righteousness, emphasizing that a life of piety is possible even in the Mesopotamian Diaspora. Most likely, the book is to be dated to the third century B.C.E., when it was composed in either Hebrew or Aramaic. Fragments of four manuscripts of Tobit from the Qumran caves are in Aramaic and one is written in Hebrew. It appears that Aramaic was the original language of Tobit and that the Hebrew texts are translations. The full text, however, was preserved only in the Greek translation.

Similar in style is the Book of Judith. This tale is set in the last years of the First Temple period, although names and details are drawn from the Persian period as well. In reality the book addresses the Maccabean era. It tells how the Jews of the Judean fortress of Bethulia (probably an imaginary name) were saved when Judith, a pious and observant Jewish woman, captivated the enemy general Holophernes with her beauty and killed him, thus redeeming her people. The book emphasizes that it was the heroine’s piety that led to her success. Judith is assumed to have been composed in Hebrew and survives in Greek and in secondary translations from the Greek. The various Aramaic and Hebrew versions of the story which circulated in the Middle Ages are either retranslations, probably from Latin, or derive from Jewish folklore and tradition.

The Septuagint’s versions of several biblical books include supplementary passages that are not found in the Hebrew originals of these texts. The Greek Esther, for instance, has six additions of this kind which fill in details presumably deemed necessary for the Hellenistic reader, whether for dramatic or religious reasons. The additions tell how Mordecai saved the king’s life and how Esther appealed to the king. The text of the king’s order to massacre the Jews is provided as well as his second letter calling on his people to support and defend the Jews. Most importantly, the prayers uttered by Mordecai and Esther are included, thus filling what some readers must have seen as an obvious spiritual lacuna in the canonical version of the book. Some of these additions were no doubt introduced by Lysimachus, an Alexandrian Jew living in Jerusalem, who translated Esther around 114 B.C.E., according to the book’s colophon.

There are similar additions to the Book of Daniel. Jewish tradition saw the book as authored by Daniel, who lived in the last years of the Babylonian Empire in the seventh century B.C.E. Modern scholars have argued that the first half of the book, dealing with the experiences of Daniel at the Babylonian court, dates to the third century B.C.E., while the remainder, describing the Maccabean period and its aftermath in apocalyptic terms, dates to the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, 167–163 B.C.E. The book survives in the original Hebrew and Aramaic and is preserved in a number of Qumran manuscripts.

Greek texts of Daniel as found in the Septuagint include three additions- (1) The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men in the Furnace provide the otherwise missing prayers in Daniel 3. (2) The story of Susanna is a beautiful didactic tale in which the pious Susanna resists the desires of two old men only to be accused by them of adultery. When his wisdom proves her innocent, Daniel’s greatness is first recognized. This tale is intended not only to teach the virtue and reward of piety and the sinfulness of adultery, but also to explain how Daniel’s wisdom came to be recognized while he was but a youth. (3) The tales of Bel and the dragon picture Daniel as proving the emptiness of these false gods and their worship. Similar compositions, related to the Book of Daniel, are known from Qumran manuscripts, especially the Prayer of Nabonidus and Pseudo-Daniel materials. Clearly composed by the time Daniel was translated into Greek around 100 B.C.E., since otherwise they would not have been included, the original language of these additions and their provenance cannot be determined.

Baruch (1 Baruch) is a hortatory work which was treated as a supplement to Jeremiah. It is a pseudepigraphon, purporting to have been written by Baruch, the scribe of Jeremiah. In the book, the Jews confess their transgressions, particularly that of rebelling against the Babylonians, which resulted in the destruction of the Temple. The book further asserts that all wisdom is from God, and that He will eventually return His people to their land. Baruch seems to be a composite of two or more parts and was probably written in Aramaic or Hebrew. Palestine is the most likely place of composition. The first part had to have been written by the onset of the first century B.C.E., but the date of the second half cannot be established. It may postdate the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., in which case the finished book would address the tragedy of the destruction. The book was read by some Hellenistic Jews on the Ninth of Av, the commemoration of the destruction of both Temples.

The Letter of Jeremiah claims to be a letter written by the prophet to the exiles from Judah who were taken to Babylonia in 597 B.C.E. A condemnation of idolatry, it was probably composed in Greek in the second century B.C.E., and a first-century B.C.E. Greek fragment was found at Qumran. The Prayer of Manasseh supplements 2 Chronicles, providing the words Manasseh, king of Judah (698-643 B.C.E.), supposedly uttered in asking God’s forgiveness for his sins.

Two wisdom texts are the books of Ben Sira and the Wisdom of Solomon. Ben Sira is a wisdom anthology, much in the style of the biblical Proverbs. It provides practical advice on interpersonal relations, especially with family, the conduct of business, and a variety of ethical teachings. This wisdom comes from God, the Creator and Ruler of all, who rewards and punishes. Ben Sira identifies God’s wisdom with the Torah, the observance of which he demands, and clearly opposes the rising tide of Hellenism. He praises all of Israel’s biblical heroes, concluding with the stately high priest Simeon the Just. The author, Joshua (or according to some manuscripts Simeon) ben Sira (or Sirach in the Greek texts), wrote in Hebrew around 180 B.C.E., and his grandson translated the work into Greek around 130 B.C.E. Some parts of the book have been preserved in the Qumran and Masada scrolls, and large parts survive in medieval manuscripts descended from the original Hebrew text.

The Wisdom of Solomon draws its inspiration from biblical sapiential texts (a technical term for wisdom materials) and their ancient Near Eastern setting as well as from Hellenistic ideas and motifs and Greek philosophical notions. This work is entirely an argument for the foolishness of ungodliness and idolatry. Although Solomon is never named in the book, its message is placed in his mouth. The message is applied first to the individual, then to the king, and finally to the entire people of Israel. Wisdom is pictured here as an emanation from God, a great light, a concept similar to the logos (divine wisdom) of Philo. At the same time the imagery used to describe wisdom is that of Proverbs. The Wisdom of Solomon was probably written in Alexandria in the Roman period, although we cannot be at all certain.

2 Esdras, also known as 4 Ezra, is the only truly apocalyptic book in the apocrypha. The angel Uriel reveals to Ezra the secrets of the approaching end of days in which the messiah will destroy all evildoers in a cataclysm. Most probably the work dates to 81–96 C.E. Originally written in Hebrew or Aramaic, a no longer extant Greek text served as the basis for the later translations which survive. This text reflects the tragedy of the destruction of the Temple and the land in the Great Revolt of 66–73 C.E. The apocalyptic, cataclysmic messianism of this work contrasts sharply with the messianism of mishnaic literature.

Finally, the apocrypha provides us with two of the most important historical sources for the Second Temple period, 1 and 2 Maccabees. 1 Maccabees is an account of the history of Judea from 175 to 134 B.C.E. It describes the background of the Maccabean revolt, the revolt itself, the exploits of Judah the Maccabee, and the efforts of his brothers Jonathan and Simon to permanently reestablish Jewish national independence and religious practice. The author paints the Hasmoneans as loyal Jews fighting against extremist Hellenizing Jews and their Seleucid supporters. 1 Maccabees was written in Hebrew in the early decades of the first century B.C.E. It survives only in the Greek text, which served as a major source for the first-century C. E. historian Josephus.

2 Maccabees is an abridgement of a lost five-volume work by Jason of Cyrene. Jason’s work and the abridgement were both composed in rhetorical Greek. 2 Maccabees details the events which led up to the Maccabean revolt and the career of Judah, concluding with his death in 160 B.C.E. As it stands now, the purpose of the book is to encourage the observance of the holiday of Hanukkah. Jason wrote not long after 160 B.C.E., and the abridger probably did his work before 124 B.C.E. Josephus did not have access to this book. To a great extent it serves as a complement to 1 Maccabees, since the two books emphasize different aspects of the revolt and the events surrounding it. On the other hand, there are many chronological and historical inconsistencies between the two works.

3 Maccabees (considered by some to be part of the apocrypha) is an unhistorical account of the deliverance of the Jews of Egypt from religious persecution, including the demand that they abandon their religion. The book draws on motifs from the biblical Book of Esther, 2 Maccabees, and other sources, and attempts to explain the existence in Hellenistic Egypt of a festival similar to Purim but celebrated in the summer.

PSEUDEPIGRAPHA

All in all, the apocrypha are a varied group of texts that have in common little more than their approximate dates of composition and their preservation in the Septuagint Bible. There is little of literary or historical significance to distinguish these texts from the pseudepigrapha except that the latter did not constitute a closed collection. Many of the pseudepigrapha found their way into the canons of various Eastern churches, usually in translations (often from earlier Greek texts) into such languages as Ethiopic, Slavonic, Syriac, and Armenian. A few of the pseudepigrapha are of major significance either for what they tell us about the period in which they were written or because they exerted influence on the later history of Judaism.

1 and 2 Enoch are totally separate works. Each, however, takes its cue from the biblical statement that God “took” Enoch (Gen. 4-24). Enochic literature, texts containing revelations to or about this enigmatic biblical figure, appeared quite early in the Second Temple period, certainly by the second century B.C.E. The impact of these traditions on later Jewish esoteric and mystical literature is significant.

1 Enoch (the Ethiopic Enoch) is an apocalyptic book in which Enoch reports his vision of how God will punish the evildoers and grant eternal bliss to the righteous. Enoch describes the angels and the heavenly retinue. He also has visions regarding the Elect, the Son of Man, and reveals a collection of astronomical data which provide the secrets of the natural order. Visions of the destruction of the sinners then occur, followed by a recounting of the history of the world as a series of “weeks.” An account of the birth of Noah and the flood concludes the book. The work is preserved in extensive manuscripts from Qumran, covering virtually all of it except chapters 37–71 (there are 105 chapters). Qumran evidence and the Greek manuscripts for parts of the book indicate that 1 Enoch is a composite of materials, mostly from the second century B.C.E., the final redaction of which must be dated after the completion of the Parables section (chaps. 37–71) sometime in the late first century C.E. Qumran versions included the so-called Book of the Giants, which is not included in the Ethiopic book.

2 Enoch (the Slavonic Enoch) is to some extent related to 1 Enoch. It is essentially a description of Enoch’s life and the lives of his descendants up to the flood. Enoch’s journey to the seven heavens is described, followed by God’s revelation of the history of the world up to Enoch’s time and the prediction of the flood. Then Enoch returns to earth, where he instructs his children in matters of belief and behavior, emphasizing the importance of his books. Finally there is a description of Enoch’s ascension to heaven. It is impossible to determine whether the book was composed in Hebrew or in Greek, or is a composite of both. The text must have been complete by the end of the first century C.E. It was passed down in two separate Slavonic recensions, one longer than the other.

The Book of Jubilees is a prime example of the genre of rewritten Bible in which Second Temple authors recast and retold biblical stories in order to teach their own lessons. Jubilees is a reworking of biblical history from the start of Genesis until the commandment of Passover in Exodus 12. The book purports to represent the revelation of an angel to Moses on Mount Sinai. Its chronology is based on the counting of years by sabbatical cycles (seven-year periods) and jubilees (forty-nine-year periods). The author fixes the dates of the Jewish festivals and gives them special significance by claiming that they were first observed by the patriarchs in commemoration of events in their lives. Indeed, the biblical heroes are pictured throughout as observing Jewish law. This work was mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and fragments of the original Hebrew text were preserved in the Qumran caves. We should note the links with the Genesis Apocryphon from Qumran. The book must have been completed in the second century B.C.E. It clearly springs from a group of Palestinian Jews who influenced the Qumran sect or were in some way related to it, but no great certainty is possible. The traditions of Jubilees played an important role in the development of the Judaism of the Falashas of Ethiopia.

The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs are a pseudepigraphic group of works in which the twelve sons of Jacob present exhortations to their children, as their father Jacob had done at the end of his life according to Genesis 49. The Testaments were preserved in their entirety in Greek and were known to the church fathers. The final text may have been worked over by a Christian editor, but the Jewish base can be easily uncovered. Each testament includes an account of the protagonist’s life in which he confesses his sins and praises his virtues, admonitions to avoid these transgressions, a prediction of the future of each tribe, including sin, punishment, and exile, and exhortation to follow the leadership of Judah and Levi. Fragments of the Testament of Levi in Aramaic and the Testament of Naphtali in Hebrew exist from both Qumran and medieval times. It seems, therefore, that the author of the Greek text used various Aramaic and Hebrew testaments (probably composed in the second century B.C.E. in sectarian circles related or antecedent to the Dead Sea sect) as a basis for his work, sometime between 100 and 63 B.C.E. His Greek text was in turn Christianized during the second century C.E. The testaments quote Enoch repeatedly and have parallels with Jubilees and the Qumran literature.

The Letter of Aristeas represents the Hellenistic milieu. In reality it is not a letter but a Hellenistic Jewish wisdom treatise presented in the guise of a report on the translation of the Torah into Greek. The work purports to have been written by the non-Jew Aristeas, an official of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.E.). The text is a tribute to Jewish law and Jewish wisdom. It tells the story of how the high priest in Jerusalem sent seventy-two scholars to Alexandria to translate the Pentateuch at the king’s request, describes how they went about their work, and affirms the validity of the translation thus produced. Much of the account is not historical. A series of embellishments from Greek philosophical traditions in fact constitutes the bulk of the text. The work is generally dated to the beginning of the second century B.C.E. It was composed in Greek, probably by an Alexandrian Jew. The very same legend is related by Philo, Josephus, talmudic literature, and the church fathers.

4 Maccabees is likewise a product of the Hellenistic Jewish world and proposes a Judaism anchored in Platonic and Stoic philosophy. The work is a discourse addressed directly to the reader and intended to encourage a Judaism in which reason ruled over the passions. Its title derives from the fact that it details the sufferings of the martyrs of the Maccabean period. In this respect it parallels 2 Maccabees. The author believes in immortality, that is, an eternal life in heaven for the pious immediately after their death. The text is probably to be assigned to the mid-first century C.E., but its place of composition cannot be determined. It was known to the church fathers, some of whom mistakenly attributed it to Josephus.

This brief survey of a few of the works of the Second Temple period, from both Palestine and the Diaspora, opens a window on the various approaches to Judaism in this important period and demonstrates the highly variegated texture of its literature. Many of these texts, and a whole host of others, were found in the Qumran caves. It is to these works that our attention now turns.

DEAD SEA SCROLLS

The term Dead Sea Scrolls designates a corpus of manuscripts which have been discovered in the last forty years in the Judean Desert in caves along the Dead Sea. The main body of materials comes from Qumran, an area situated near the northern end of the Dead Sea, 81/2 miles south of Jericho. The scrolls were collected by a sect of Jews in the Greco-Roman period. They were hidden in ancient times and rediscovered in 1947, when a young Bedouin shepherd entered what is now designated as cave 1 and found several pottery jars containing leather scrolls wrapped in linen cloths. Starting in 1951 a steady stream of manuscripts was brought to light.

Actually, this was not the first discovery of its kind, for several accounts preserved by the church fathers indicate that scrolls were unearthed in the Dead Sea region as early as Roman and Byzantine times. Medieval accounts speak, as well, of an ancient Jewish sect of cave dwellers in the area.

The dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls was a subject of controversy from the very beginning. Some regarded the new texts as medieval Karaite documents. Others held that they dated from the Roman period, and some even thought they were of Christian origin. The dating question was resolved by means of several kinds of evidence.

Of primary importance was the archaeological excavation of the building complex on the plateau immediately below the caves. In the view of most scholars, this complex was connected with the scrolls. The residents of the complex copied many of the scrolls and were part of the sect described in some of the texts. Numismatic evidence has shown that the complex flourished from around 135 B.C.E. to 68 C.E. Occupation was interrupted only briefly by an earthquake in 31 B.C.E.

Similar conclusions resulted from carbon-14 dating of the cloth wrappings in which the scrolls were found. Studies of the paleography (the form of the Hebrew letters in which the texts are written) have supported much the same dating. Scholars have identified the scrolls, therefore, as the library of a sect which occupied the Qumran area from after the Maccabean revolt of 168–164 B.C.E. until the Great Revolt of 66–73 C.E.

The many scrolls found in the Qumran caves can be divided into three main categories- biblical manuscripts, apocryphal compositions, and sectarian documents. Fragments of every book of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) have been unearthed at Qumran with the sole exception of Esther. Among the more important biblical scrolls are the two Isaiah scrolls (one is complete), and the fragments of Leviticus and Samuel (dated to the third century B.C.E.). The study of the biblical texts from Qumran has given rise to a theory of local texts. This theory maintains that at the root of the variations are three recensions of the Hebrew Bible- One is the Palestinian, from which the Samaritan Pentateuch is ultimately descended. A second is the Alexandrian, upon which the Septuagint is based. Finally, there is the Babylonian, which is the basis of the Masoretic (received and authoritative) Hebrew text fixed by the tannaim (the Mishnaic rabbis) in the late first century C.E. While the division of biblical manuscripts into three basic families has much to recommend it, it is unlikely that these text types originated outside of the Land of Israel. Further, recent studies show that the proto-Masoretic texts are the most common and that only a few proto-Samaritan or Septuagintal texts can be identified. In addition, there are a substantial number of manuscripts written in a form peculiar to the Qumran sect.

The contribution of the biblical scrolls to our understanding of the history of the biblical text and versions cannot be overstated. We now know of the fluid state of the Scriptures in the last years of the Second Temple. With the help of the biblical scrolls from Masada and the Bar Kokhba caves, it is possible to trace the early stages of the standardization process that ultimately led to the final acceptance of the Masoretic (received) Hebrew text as authoritative by the first-century rabbis. We can understand as well the manner in which local texts played a role in this history, and finally, the nature of the Hebrew texts which served as the basis for the ancient translations of the Bible.

By far the most interesting materials among the Dead Sea Scrolls are the sectarian compositions. These are the writings of the sect which inhabited Qumran. They consist of biblical commentaries and documents outlining the regulations by which the sect was governed, its approach to Jewish law, and its messianic yearnings.

The Pesharim were the sect’s biblical commentaries. They seek to show how the present pre-messianic age (i.e., the era in which the scrolls were written) is the fulfillment of the words of the prophets. As such, they provide an important source for an understanding of the sect’s self-image and view of its own history and place in the general society. These Pesharim include commentaries to Habbakuk, Nahum, and some of the psalms. It is only in the commentaries that we find the names of actual historical figures who lived in the period during which Qumran was occupied.

Another of the manuscripts in the Qumran collection was the Damascus Document, also known as the Zadokite Fragments. Two copies of this work, dating from the tenth and twelfth centuries C.E., had been among the Hebrew manuscripts that Solomon Schechter had found in the genizah (“storehouse”) of the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, and brought to Cambridge University in England in 1896. Until the discovery at Qumran the Damascus Document, which detailed the life and teachings of an otherwise unknown Jewish sect, had been regarded as a strange composition of quite uncertain provenance. It now became apparent that it had been written by the Qumran sect and thus that at least one Dead Sea text had continued to circulate in the Middle Ages.

Admission into the Qumran sect, the conduct of daily affairs, and the penalties for violating its law are the subjects of the Manual of Discipline (Rule of the Community). This text makes clear the role of ritual purity and impurity in defining membership in the sect, and, as well, details the annual mustering ceremony and covenant renewal. Appended to it are the Rule of the Congregation, which describes the community at the end of days, and the Rule of Benedictions, which contains praises of the sect’s leaders.

The Thanksgiving Scroll contains a series of poems describing the beliefs and theology of the sect. Many scholars attribute its authorship to the so-called teacher of righteousness (or “correct teacher”) who led the sect in its early years.

The Scroll of the War of the Sons of Light against the Sons of Darkness details the eschatological war. In it, the sect and the angels fight systematically against the nations and the evildoers of Israel for forty years, after which the end of days dawns. This scroll is notable for its information on the art of warfare in the Greco-Roman period.

Unique is the Temple Scroll, an idealized description of the Jerusalem Temple and its cult, including, as well, various other aspects of Jewish law. The text takes the form of a rewritten Torah, and the various verses dealing with the subjects at hand are harmonized into one consistent whole. Debate surrounding this text concerns the question of whether it is actually a sectarian scroll or simply part of the sect’s library like the biblical and apocryphal compositions described above. Numerous smaller texts throw light on mysticism, prayer, and sectarian law. Many of these texts have not yet been published or await thorough study.

Exceedingly significant is a still unpublished text called the Miqsat Ma’aseh Ha-Torah (literally, Some Matters Relating to the Torah), referred to in chapter 6 in connection with the Sadducees. Described as a “halakhic letter,” it is written in the form of a letter from the leaders of the sect to the Jerusalem establishment, outlining the disagreements over Jewish law and Temple practice that had caused the sectarians to secede. The text indicates that there were close connections between the founders of the sect and the Sadducean priesthood, and demonstrates, as we have noted, that views later attributed to the Pharisees governed actual practice in the Jerusalem Temple in Hasmonean times.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have illuminated the background for the emergence of Rabbinic (Mishnaic) Judaism and early Christianity. While many of the detailed comparisons that have been suggested do not have adequate support, the more general conclusions reached by scholars are very important. We now know that as a result of the Great Revolt of 66–73 C.E., and to some extent even in the years preceding it, Judaism was moving toward a consensus that would carry it through the Middle Ages. As Talmudic Judaism emerged from the ashes of the destruction, groups like the Dead Sea sect fell by the wayside. Nonetheless, the scrolls allow us an important glimpse of the nature of Jewish law, theology, and eschatology as understood by one of these sects.

The scrolls show us that the Second Commonwealth period was an era in which Jews engaged in a vibrant religious life based on study of the Holy Scriptures, interpretation of Jewish law, the practice of ritual purity, and messianic aspirations. Jewish practices known from later texts, such as the putting on of tefillin (phylacteries), daily prayer, and grace before and after meals, were regularly practiced. Rituals were seen as a preparation for the soon-to-dawn end of days which would usher in a life of purity and perfection.

The scrolls, therefore, have shown us that Jewish life and law were already considerably developed in this period. Although we cannot expect a linear development between the Judaism of the scrolls and that of the later rabbis, since the rabbis were heir to the tradition of the Pharisees, we can still derive great advantage from the scrolls in our understanding of the early history of Jewish law. Here, for the first time, we have a fully developed system of postbiblical law and ritual.

At the same time, it is now clear that the sect, emphasizing as it does the apocalyptic visions of the prophets, provides us with a background for understanding the emerging Christian claims of messiahship for Jesus. The Dead Sea Scrolls are especially illuminating with regard to the world-view of early Christianity. This is true despite the fact that the Dead Sea sect, and for that matter all the known Jewish sects of Second Temple times, adhered strictly to Jewish law as they interpreted it.

SUMMARY

This survey of the literary heritage of Second Temple times gives only a small indication of the religious and intellectual ferment of the age. Varying interpretations of the biblical tradition were constantly interacting with each other and with Hellenistic notions in the marketplace of ideas. While this process must have involved intimately only a minority of the Jewish population of the Land of Israel and the Diaspora, events soon to burst upon the scene would bring ideological differences to center stage. Many ideas found in the texts surveyed here would become central to the ongoing debate among Jews regarding freedom from foreign domination, revolt, messianism, and redemption. Jews would soon face the challenges of Roman rule and the rise of Christianity.

Nice work, it’s appreciated.

Thanks for your work!