Tomb of King Tutankhamen, 1323 BCE

King Tutankhamen ruled Egypt for nine years, from approximately 1332 to 1323 BCE. He ascended the throne at age nine, and he remained in power until his sudden death at age 18.

His tomb was discovered on November 22, 1922, by Howard Carter, an English archaeologist and Egyptologist, in the Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Egypt. He described the discovery thus-

“At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flames to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues and gold – everywhere the glint of gold.

For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, ‘Can you see anything?’ it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.”‘

Tutankhamen’s Chariot 1

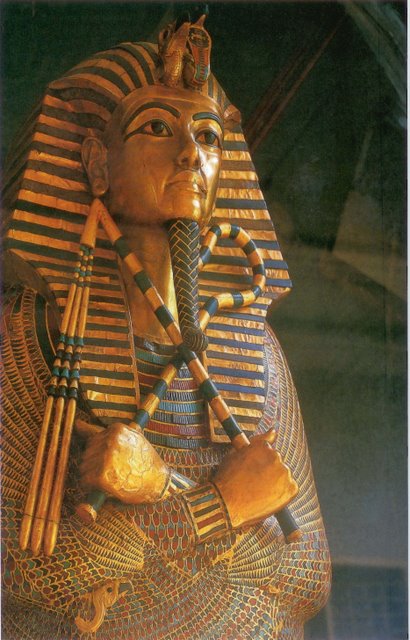

Tutankhamen’s gold mask

The gold mask which covered the head and shoulders of Tutankhamen’s mummy has become an instantly recognizable image of ancient Egypt. It represents the king wearing a striped royal headdress with the head of a vulture and a cobra (the two protective goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjit), a beard, and a broad collar. The mask retains the likeness of the person’s most important characteristic, the face.

Tutankamen’s mask was made of two sheets of gold which were hammered into shape, shaped, inlaid and burnished. The yellow of gold and the blue of lapis lazuli faience or glass dominate the color scheme of the mask. The kings eyes are inlaid with quartz and obsidian, with spots of red painted in their corners. The eyes are extended by inlaid cosmetic lines. The king’s ears were pierced. The headdress is rolled up into a pigtail at the back; its stripes are inlaid with blue glass. The shoulders and the back of the mask are inscribed with a text taken from the Book of the Dead, a collection of religious spells which were thought to be useful to a deceased person in the afterlife. The face of the king, especially in profile, bears a striking resemblance to his representations in reliefs.

Painted box from the tomb of Tutankhamen

Wood overlaid with gesso and painted.

Egyptian furniture did not include wardrobes. Instead clothes were stored in chests and boxes. One of Tutankhamen’s boxes is decorated with exquisite scenes painted on all its sides as well as the lid. Although the box is quite large the complexity and detail of the scenes makes them miniatures when compared with tomb paintings. On the long sides of the box the king is shown in his chariot charging the Syrians and Nubians, i.e. the two potential enemies in the north and the south. On the lid the king is again in his chariot, this time in two scenes of hunting wild animals. On the two short sides he is in the guise of a sphinx, trampling over fallen enemies. These are the traditional themes reaffirming the pharaoh’s domination over external enemies and the forces of nature but they are presented in a way which became standard in the New Kingdom. The chariot was only introduced to Egypt in the period preceding the rise of the New Kingdom. The confused melee of fallen enemies is similar to the depictions of battle scenes on temple walls. There is, however, little doubt that Tutankhamen was personally never involved in wars against the Syrians or Nubians.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Malek, Jaromir, Egypt; 4000 years of Art. London- Phaidon Press, 2003.

See also-

What do you want to know?

Ask our AI widget and get answers from this website