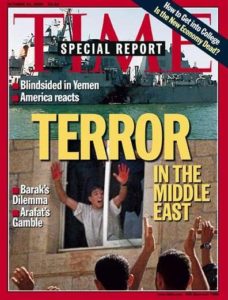

Terror in the Middle East, Time Magazine, Oct. 23, 2000.

Fires of Hate

Just when the world was beginning to feel like a safer place…

The centuries-old ethnic strife roiling in the Balkans was being joyously transformed by the miraculous power of democracy. The gunpoint tension on the Korean peninsula was being dissipated by the democratic reformer Kim Dae Jung in the south, who last week won the Nobel Peace Prize, and his unlikely partner in the north, Kim Jong Il. And the unholy struggle in the Middle East looked, for a few moments at least, as if it was being narrowed mainly to semantic nuances about control and sovereignty over a mere 35-acre mount of land in Jerusalem.

Then came the explosions and mutilated bodies.

In the span of a few hours last Thursday, Middle East gunfighting and its bastard cousin terrorism burst back into our lives with split-screen bulletins and double-deck headlines that hammered home again both the volatility of that region and the vulnerability of the entire world. It was a reminder that the horror facing the 21st century will be the one left unresolved in the 20th- after the end of the great confrontations between shifting alliances of nation-states, we are still faced with the bloody terrors wrought by ethnic, religious and tribal hatreds.

The Middle East violence began with skirmishes after Israeli superhawk Ariel Sharon visited the disputed holy site in old Jerusalem, escalated with the gut-wrenching televised death of a 12-year-old Palestinian boy shot as his father tried to shelter him, and then erupted when seething Palestinians (whom Yasser Arafat seemed at first unwilling and then unable to control) murdered and mutilated two Israeli soldiers. Prime Minister Ehud Barak ordered a military retaliation, which halted his lonely reach, or perhaps overreach, for a comprehensive peace.

The same afternoon that Israel’s helicopters were shelling near Arafat’s compound, suicidal terrorists on a small boat crept up to an American destroyer refueling in Yemen, stood at attention and set off an explosion that killed 17 crewmen. Later came a less effective attack on the British embassy in Yemen, along with fears that a new terrorist jihad could threaten innocents around the world.

The waves reached America’s financial markets, already unnerved by signs of weakness in the New Economy. Consumers and businesses coping with higher energy prices faced a winter of uncertainty about oil.

There were ripples as well for America’s tight presidential race. Suddenly the stakes were higher than mangled syllables and exaggerated anecdotes. With the reminder that the world was indeed still a very dangerous place, did George Bush’s passing performance on foreign policy in last week’s debate now seem adequate enough? Does his reassuring team of Dick Cheney and Colin Powell trump Al Gore’s expertise? How do we feel about Gore’s rather expansive vision of national interests and the value of nation building now that the threats suddenly seem more vivid?

In the meantime, a pride of diplomats, crossing paths and wires in a dark version of a play with no plot, suspended their disjointed efforts for a grand Middle East settlement and settled, instead, for a hastily arranged meeting to stanch the bloodshed. Buried in the rubble was not just the peace process, it was also our dreamy view of what the world was becoming. Confronted again with pictures of flag-draped coffins and mutilated bodies, with the sounds of random gunfire and angry chants, the world had to readjust to the fact that not every problem is solvable, that the global tide of peace is not inexorable, and that progress does not inevitably make civilizations more civilized.

Breaking Point

By Lisa Beyer

It was late morning when Brigadier General Gadi Aizenkott appeared at the door of his boss, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, with dreadful news. Two Israeli reserve soldiers had wandered by mistake into the West Bank city of Ramallah and had been lynched by an ecstatic Palestinian mob. They were beaten, stabbed–one was tossed out a second-story window–and defiled again. As usual on a Thursday, Barak, who serves as his own head of the Defense Ministry, was at its headquarters in Tel Aviv, dressed for the part in an open shirt and windbreaker. Immediately, he summoned his top commanders into the room. Amid some of the most ferocious violence ever between Israelis and Palestinians, Barak–until the visit by Aizenkott, his military secretary–had been struggling to avoid an escalation that would imperil the peace process he hoped would bring a lasting end to such mayhem. But the Ramallah attack was “too much,” says Deputy Defense Minister Ephraim Sneh. “That was the end.”

From his generals across the table Barak wanted advice on where to strike back. The officers, who had been chafing at a policy they considered too restrained, were happy to oblige with a detailed target strike list. Within hours, Israeli Cobra attack helicopters were in the air over the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, unleashing their missiles on five carefully chosen Palestinian security sites, one of them close enough to rattle the Gaza headquarters in which Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat was holding court. The Palestinians screamed that Barak had declared war. “It’s nonsense, bullshit and propaganda,” Barak told CNN. “It was not a millionth of what we can do if it was really a war.”

War is an awkward term to apply to a conflict in which the balance of forces is so lopsided. Israel’s military is among the world’s most heavily armed and proficient. Arafat’s scruffy troops have neither tanks, artillery nor aircraft. But if it wasn’t quite war last week, it was nevertheless a fierce mess. The exhaustive, seven-year effort to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through negotiation has withstood great tests, but none as scorching as this. While regional leaders agreed to a summit this week in Egypt, their ambitions were contained by the need to squelch the bloodletting. After two weeks of violence, neither Israeli nor Palestinian leaders–nor the U.S. officials who have painstakingly nurtured their talks–held out much real hope of restoring the momentum toward peace. “Something was torn here, and it seems as if the genie left the bottle,” said Israeli Justice Minister Yossi Beilin.

The tortured relationship between Israelis and Palestinians was not the only thing at stake. While there remained a sound logic against a new, widespread Middle East war–namely that the Arab armies are in no shape to take on Israel’s–the furious race of developments left regional leaders with a creepy hint of that possibility, especially after a new front opened up when Hizballah militiamen in Lebanon breached the border to kidnap three soldiers from Israel. Barak holds Syria, the real power in Lebanon, responsible and said in an interview with TIME that Israelis would “keep for ourselves the right to respond.” He added, “We will know when and how to do it.”

Throughout the Arab world, supporters rallied behind the Palestinians, protesting in mass demonstrations against Israel and, in some cases, its chief ally, the U.S. The terrorist bombing of a U.S. destroyer in Yemen last week that killed 17 American sailors was a reminder of how widespread that anger can be.

The disaster in Ramallah–and Israel’s tough response–was what elevated the crisis to calamity. The problem started when Vadim Norzich, 35, and Yossi Avrahami, 38, made a wrong turn as they drove to their army base in the West Bank after being called up for duty like hundreds of other Israeli reservists last week. Ironically, they were both drivers in the army. In the city of Ramallah, they happened upon a funeral procession for a 17-year-old boy shot the day before by Israeli troops. Identifying the two as Israelis–the giveaway was the yellow license plate on their car–the impassioned crowd went after them. A rumor spread that they belonged to Israel’s so-called Arabized forces, who disguise themselves as Palestinians to hunt radicals on Israel’s wanted list.

Palestinian police took the two reservists into a nearby station and, for a time, kept the mob at bay. But some of the vigilantes entered through a second-floor window. Through the opening, TV crews filmed them stabbing and pummeling the Israelis inside. One of the attackers returned to the window to proudly show the jubilant crowd his blood-soaked hands. Moments later, the body of one of the soldiers came flying out of the window, smashing into the ground below, where the mad crowd danced, beat it some more and celebrated before parading the corpse through the streets. Palestinian police handed over the other soldier, badly mutilated, to a nearby Jewish settlement just before he died.

The killings were about as raw a display of atavistic inhumanity as one could imagine. Palestinians, however, were quick to point to the incredible disparity in casualties–more than 100 dead Palestinians versus six dead Israelis–as an outrage. Worse atrocities than the Ramallah lynchings have been committed before in the conflict, on both sides, but never on film. “Morally, we had to retaliate,” said Israeli military chief Lieut. General Shaul Mofaz. “It was a supreme commandment even.” In preparing his attack, Mofaz worked from a list of 30 possible targets, all facilities of the Palestinian Authority. Among them was Arafat’s headquarters in Ramallah. On a 30-in. flat screen next to his desk, Mofaz checked the live reconnaissance feed from an Israeli drone flying over the area and saw that Arafat’s car was parked outside. He knew the Palestinian leader was actually in the Gaza Strip. But in any case, he didn’t want to strike Arafat’s headquarters. He wanted a strong response, not a conflagration.

In the end, Mofaz chose and Barak approved strikes on the police station where Norzich and Avrahami were attacked, the parking lot of a nearby police station, the antenna of the broadcasting center in Ramallah that had been spouting anti-Israeli invective, a police building in the Gaza Strip used by Arafat’s Tanzim paramilitary (which has orchestrated much of the recent unrest) and a Gaza port where the 12 boats of the Palestinian navy were docked. The last was an odd choice, except for the fact that it was just 100 yds. from Arafat’s office. Later, the Israelis attacked the police academy in Jericho, after Palestinians torched an ancient synagogue there. In each case the Israelis notified Palestinian officials of the site selected before the Cobras flew in, so that it could be emptied, and then the Israelis monitored the evacuations by drone. The Cobras shot innocuous machine-gun fire as a final warning before unleashing their real payloads. In the event, at least four Palestinians were injured in the raids, but none were killed. It was a powerful hint of what the Israelis might do if provoked. “We barely used 1% of our power,” said Mofaz.

When it came to making a truce, however, the two sides appeared to be using about 0% of their power. It wasn’t from lack of encouragement. Since the collapse of peace talks at Camp David in July, the U.S. has been losing credibility with Arafat–something that opened the door to a whole host of other diplomats. As a result, when last week’s fighting began to look truly out of control, everyone from U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan to British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook to Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov rushed to toss in his 2[cents]. The diplomacy that followed was chaotic and–for the White House at least–downright frustrating. The heavy lifting of trying to bring the two sides together was handled by Annan, who spent a good part of the week dashing from meeting to meeting. But his job was complicated by a constant need to triangulate with other countries.

Annan had an eager partner in Clinton, who hit the 100-days-left-in-his-presidency mark on the day of the Ramallah lynchings. Clinton, desperate to get the situation bottled up, became like a “case officer,” aides say, making dozens of calls a day and completely reorienting his schedule to focus his time on finding a quick solution.

The idea brewing inside the White House was to try to craft a “de-escalation strategy” that could walk both sides back to the point where they could at least talk peace. That was a tall order, given that the Ramallah murders and Israel’s sharp retaliation were only the pinnacle of a fortnight of astonishments and new lows. On Oct. 7 a Palestinian mob demolished Joseph’s Tomb, a Jewish holy place within the West Bank city of Nablus, after besieged Israeli troops withdrew from the site with assurances that Arafat’s gendarmes would protect it.

That naked display of violent intolerance added a new dimension to the set-to. In retaliation, Jews in Tiberias vandalized an ancient mosque. Even the funeral of a slain Jewish settler was not spared from assault. As the procession moved along a West Bank road, Palestinians stoned the mourners, some of whom in turn whipped out assault rifles and opened fire.

Assuming peace talks could somehow be resumed in earnest, they would surely be colored by the furies set loose in recent days. Many of the assumptions that enabled the Camp David talks to get as far as they did have been blown apart. Would either side now contemplate letting the other guard any of its holy places? Could cooperation between security forces ever be restored to the point of providing any real benefit? Could Israelis again consider allowing some Palestinian refugees to repatriate to Israel–having come to see the current Israeli Arabs as traitors in their midst? “Even if we eventually find some formula, the scar won’t go away,” says Justice Minister Beilin. “We will never forget this nightmare.”

Arafat has been signaling for months that he doubts he can get a deal he can live with from the Israelis. And now his aides are indicating they won’t be satisfied with a truce alone. “We want an insurance this time…that Israel will never repeat what it did in the missiles and the tanks and the choppers,” said Saeb Erakat, a top aide to Arafat. Barak, as discouraged as he was last week, wasn’t quite ready to quit. “We will never lose hope of making peace with our Palestinian neighbors,” he said. “They are here forever, as we are.” Until now, Barak has felt it imperative to make a final peace deal while Arafat, 71 and ailing, was alive, believing that only Arafat had enough credibility with the Palestinians to make the necessary compromises. That thinking has altered. “A leadership could change its mind,” he said. “It could be replaced.” Barak, last week, was clearly exhausted by Arafat. The question was whether the two sides were more exhausted by violence than by each other.