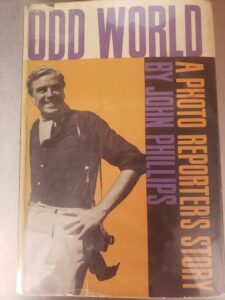

Odd World: A Photo Reporter’s Story, John Phillips, 1959.

“I’m like a Genoese mercenary. I get paid to do a job. I calculate the risks, and while I may get killed, I’ll never get ulcers.”

“I’m like a Genoese mercenary. I get paid to do a job. I calculate the risks, and while I may get killed, I’ll never get ulcers.”

These words are John Phillips’ own summing up of his quarter of a century of taking news pictures. Born in Algeria of an American mother and Welsh father, Phillips has lived and worked all over Europe, the Middle East, Africa and South America. This is the story of his world of violence, a world at war or at dubious peace, and of the curious and extraordinary men and women who make news for modern cameramen.

Phillips was the first man to be called a “reporter-photographer” by Life. He covered the Nazi occupation of Vienna and the Sudetenland. He photographed Yugoslav partisans behind the German lines. He took the famous picture of Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill at Teheran. He covered the trial of Mikhailovich, the Israeli-Arab fighting in Jerusalem, and Khrushchev’s visit to Tito.

The stories behind these pictures make up this book. Along with them are the stories of dozens of personalities such as King Farouk, Saud of Arabia, Glubb Pasha, Saint-Exupery, Mike Todd. Here are the stories of a jeep trip through Eastern Europe the summer the war ended, of a day as Tito’s personal guest on his island in the Adriatic, of finding ex-premier Skladkowski of Poland learning Hebrew in a Tel Aviv boardinghouse and hoping to become an air-raid warden. Here is a running account of our times, told by a reporter who uses his eyes and a pencil as well as he uses his camera.

Pages 241-250

On May 14 the stage was set for the curtain to run up. Early that morning the British High Commissioner, Sir Alan Gordon Cummingham, left Government House on the Hill of Evil Counsel outside Jerusalem. Sir Alan was driven to the airport in a bullet-proof Daimler. On landing at Haifa he boarded the cruiser Euryalus as a band struck up “The Minstrel Boy.” On the stroke of midnight H.M.S. Euryalus, floodlighted by her destroyer escort’s searchlights, crossed the three-mile limit into international waters. The British mandate in Palestine had ended.

All that day Arab Legion units had wound their way down to the valley toward Allenby Bridge, and the Bedouin warriors performed their wild war dance under Ab’s excited eyes. At dawn on the fifteenth, my Arab Legion kouffieh flying, I drove into Palestine.

Thoughtfully Glubb had equipped the correspondents with Legion uniforms and issued us Legion pay books for identification; now we only risked death or injury from the Israelis. In my new security I drove off to see what Fawzi’s Liberation Army was up to. Fawzi’s objective was to take the two Jewish settlements of Atarot and Neve Yaakov which controlled the main road to Jerusalem. Now after two days of Arab looting Atarot existed no more. Bloated dead horses and Holstein cows, ready to burst, lay in the smouldering ruins while Arabs, like junk men, picked around debris scattered with sheet music of Mozart’s Magic Flute and airmail letters blown along by the wind.

I found the Victory Cafe at Ramallah, on the road to Latrun, a gossip center for Fawzi’s warriors. There they rested on their rifles and discussed the battle of Neve Yaakov which was in progress. Some of these warriors, refreshed, climbed into a truck and drove off to have a shufti, a look, and I went along with them. On our way we passed a gun shelling Neve Yaakov, which was perched on a hill across the valley and dominated by a concrete schoolhouse, now turned into a fort. Farther up the road, coming around a bend, we drew Israeli fire from Neve Yaakov. This made my travelling companions scream loudly and the truck was hurriedly backed out of sight and safety.

During the night the Israeli forces withdrew from Neve Yaakov and at dawn I found Titch, the spokesman of Frank’s irregular transfers, at the entrance of the settlement. He was shouting, “Keep the buggers out, mon,” to Arab constables who were beating off swarms of screaming Arabs impatient to loot.

“The whole bloody place is mined,” Titch explained to me, and Frank himself disconnected a wire from a milk churn filled with nuts and bolts.

“Keep that bugger out, mon,” Titch warned when an impatient Arab, unable to contain himself, clawed his way past a guard. “He’s going to get his balls blown off.”

There was a bang and a howl as the Arab leaped on a booby trap. A hush came over the crowd as he was carted off.

“That’s going to quiet them for a bit,” Titch said, grinning.

I noticed that Frank’s Band had acquired a new recruit, a twenty-one year old German SS man who had escaped from prison camp. I watched as Frank’s men professionally worked their way up the deserted lane, defusing the heavily mined and booby-trapped settlement. Low houses lined this lane, and as the sun slowly rose above the hills its rays cast sharp shadows on the body of an Arab Liberation soldier who had succeeded in breaking into the settlement the day before. From time to time, Titch’s rough admonition could be heard above the hubbub of the impatient crowd.

“Verdammeter Hund!” the German shouted, trying to reach for his gun with his left hand as he fought off a dog whose teeth were sunk in his right wrist. This occurred after he opened a door he had just unwired, to look inside for valuables, and found instead an angry police dog.

When he heard the German language, the dog let go and wagged his tail.

“Was ist los?” the German exclaimed in surprise.

“His master must have been a German,” I suggested.

“Ach so, a German Jew,” he said thoughtfully as he wrapped a handkerchief around the wrist.

“This is thirsty work,” Frank remarked. “Have a beer.” He fired into a can of Budweiser and a column of foam shot up.

The young German came out of a house holding a gray suit on a hanger. “Frank,” he called out, “do we take?”

“Don’t be daft, mon,” Titch advised him. “If it doesn’t fit, it’s worth at least three quiddels.”

“I couldn’t wear it,” the German said, “although I need a suit and this one looks clean.” He held it at arm’s length and stared at it, as though puzzled for an explanation. “It’s my upbringing,” he said at last.

“Come, lads,” Frank ordered, as Titch carted off a case of liquor. “Let’s get out before these buggers get wild and it gets dangerous.”

They departed, and I climbed on the roof of a house commanding the lane which led to the gates. No sooner was I there then they came in a frantic rush of screams, sweat and rags, stumbling over each other. Their eyes were popping out of their heads and their bare feet pounded the ground. Those in front dived into the houses as the others rushed on. Soon they milled around Neve Yaakov like ants picking a bone clean. They emerged from houses carrying desks, chairs, pots, pans and beds. Here one grabbed a parasol; there another, a pair of boxing gloves around his neck, led off a cow whose udders were ready to burst; a third, balancing a sewing machine on his head, tried to grab a blanket from a fourth. Those loaded with loot fought their way down the stream of newcomers who kept arriving. These latecomers broke off the doorknobs, unhinged the doors and tore off the aluminum roofing. One, unable to yank open the steel door of the high-tension box, fired into the lock. The ricochet hit an Arab, who was trampled by others as they rushed out screaming, “Snipers, snipers!” In this frenzy, two more Arabs got wounded and I hurriedly took off.

The Arab Legion, after taking “the best military defense positions,” was now besieging the Jewish quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. Major Abdullah Tell, in command of this operation, had established his headquarters where Pontius Pilate once resided, at the First Station of the Cross.

Curious to see this army, the only one capable of putting up any real fight against the Israelis, Don Burke of Time, Nassib—our Arab interpreter—and I drove up from Jericho. From a sweeping bend in the road we saw the New City of Jerusalem, where the Israelis were besieged, spread out before us in the distance. An Arab Legion army car, with its back to the Mount of Olives, was shelling the New City. A large Arab gathering stood in the open nearby and watched this bombardment with satisfaction. Their nonchalance convinced us they were out of Israeli range. But no sooner had we joined this crowd than I heard a sharp crack like a walnut split open. Looking around, I saw that an Arab had been hit in the head. Burke, Nassib and I ran off the road, toward the Mount of Olives, in search of a commanding view to get pictures of this scene. As often happens when urgency of time and fear are combined, certain impressions become blurred while others stand out. I remember holding the cameras that dangled from my neck, so that they would not knock against each other as I stumbled over uneven ground. I believe we were in the Jewish cemetery. Ahead of us was a wall. When we got there we were dripping with perspiration, although it was still chilly. Slowing up to regain our breath, we noticed a gap in the wall. This gap looked out toward the New City and it would expose us to Israeli fire when we passed. This was Nassib’s first war. He stopped, lighted a cigarette, and leisurely sauntered across the opening. Don and I glanced at each other and shook our heads. Don slung his musette bag across his wide shoulders, took a deep breath and threw himself across. As he did, dust rose where bullets hit dry earth. They only just missed the seat of his pants, it seemed to me. The Israelis had spotted our red-and-white kouffiehs and no doubt mistook us for the gun direction of the armored car. Now it was my turn and I suddenly felt someone in the New City was waiting for me. From the shade and protection of my wall I stared at the patch of sunlit earth that I had to clear. I wiped my face with a corner of my kouffieh. I hesitated, knew I could not make it, and slumped to the ground ashamed of myself. With the rise of the land, the wall across the gap offered much less protection, and Don and Nassib were having a bad time there. As I waited Don suddenly hurled himself back where I sat. He landed with such force that the shoelaces of his GI boots snapped. Don shook his head, opened his musette bag and fished out another pair as though this were a matter of course. Nassib joined us and we got out in a hurry.

In civilian clothes Major Abdullah Tell would have passed unnoticed in the City of London. His mustache was very English, and so was his self-control. Doctor Moussa Husseini, the Arab civilian representative, who also had an office at the headquarters, was extremely suave—Continental, the English would have said. In appearance these two had little in common with the Arabs who surrounded them—the hysterical young Egyptians who kept putting on and taking off their ammunition bandoleers; the swashbuckling Iraqis with kouffeihs draped like turbans; and the pudgy city fathers from Amman who kept asking anxiously about the progress of the war. In the midst of all this hubbub boys served Turkish coffee and the phone rang incessantly. When a call came from King Ab, Major Abdullah Tell ordered silence and stood up to inform his agitated monarch that the Jewish quarter in the Old City was still holding out.

It was there at Major Tell’s headquarters that I met Peter. He had come back to report an attack being made that afternoon against a synagogue in the Jewish quarter of the Old City. On first impression Peter looked younger than he was, due to his slim boyish build. He had, however, a tired, almost haunted look about his eyes. Dressed in Army pants and a windbreaker, he wore a woolen scarf loosely around his neck with a certain elegance. His rifle was slung over his shoulder.

“Something must be done at once,” he told Abdullah Tell. “The synagogue is so full of looters we have no room to fight.” Abdullah Tell sighed and Peter turned to me and added, “You should see the silly bastards.”

Peter disapproved of looting; he was a killer. The only clothes he owned were those on his back, and he slept where night and fatigue caught up with him. He would disappear without a word and show up a day or two later, unexpectedly, without a word about where he had been. He also vanished at mealtimes, and I don’t recall ever seeing him eat. He knew his way around the maze of the Old City on the darkest night. Lightfooted like a cat, he picked his way around the debris as he led me where he knew I would get good pictures.

One morning we crawled on a roof which overlooked the sandbagged ramparts manned by the Arab Legion. Lying on my stomach, I was fitting into my camera sights the legionnaires behind their sandbags and getting the King David Hotel and the YMCA in Israeli territory in the background, when Peter said, “The Arabs have had it. It’s going to be a mess soon.”

I agreed and released my shutter. “I’ve got to get out before that,” he went on, and again I agreed and rewound my shutter.

I was shifting to get another angle when Peter said, “I’ll need money to get out, so I’ll sell you my story.”

I said, “Yes,” and tried to make out the flag fluttering from the King David.

“It’s going to cost you a lot, though,” Peter said after a pause, “because this money’s got to take me where there are no Jews.”

“Like the moon,” I suggested.

Peter did not laugh. “There must be someplace. How about Cape Town?”

“Hardly,” I said.

“There must be a place where I’ll be safe.” I could feel the desperation in his voice. “I pulled Ben Jehuda.”

I sat up and then, remembering I was still an Israeli target even if I had removed my checkered kouffeih, flopped down. “Is that the story you want to sell me, Peter?” I asked.

He nodded. “I was in Damascus yesterday to see the Grand Mufti. When he refused to pay the five hundred pounds he had promised, I told him I’d sell you the story.”

“Peter,” I said, “Over fifty people, including children, were killed when that truck loaded with explosives went up. You wounded nearly as many and flattened a couple of buildings. How do you expect a magazine to buy such a story?”

Some homemade Israeli mortars began to land. “I think we’d better get out,” I suggested. Peter nodded.

Despite Peter’s certainty of an Arab disaster, a few days after our conversation the Jewish quarter of the Old City surrendered. It was only a small pocket of resistance and Peter was unimpressed. He stood silently while a group of us watched the negotiations take place in a street which led down to the Jewish quarter from Zion Gate. The terms of surrender were finally signed in the presence of Dr. Pablo de Azcarate, a Spaniard from the United Nations Security Council’s truce commission.

As both parties signed the articles of surrender, Peter came to life. Leaning over he whispered to me, “There’s only one bastard I’m interested in. He deserted from a Suffolk regiment to join the Jews. I’m pretty sure he’s still alive.”

To prevent looting and the murder of prisoners, Major Tell imposed a curfew on the Arab civilians. The young Haganah commander leading the way, we followed him into the Jewish quarter. It was a honeycomb of small crowded stone houses which faced one another across long narrow courtyards and surrounded Ashkenazi Square. The first thing I noticed on entering the square was the squat synagogue, which stood out like an amputated thumb, with its cupola blown off. On one side of this wide square the Haganah fighters were drawn up in a loose formation. Their weapons, helmets and what remained of their ammunition were stacked up not far from them. They had the dull look and the slow movements of men who have had little sleep and have been under constant fire. Their Western appearance was in sharp contrast to the civilian Orthodox Jews who stood nearby.

These civilians with beards and side curls, wide-brimmed black felt hats and long black coats were members of families which had been residing in Ashkenzi Square for centuries. Now they were being given an hour to move. Fatalistically they all—the elderly men, the women and children—waited for the signal to be evacuated to Zion Gate, where they would be admitted to the New City and swell the besieged population. What they could carry of their belongings bulged out of sheets fastened into clumsy bundles. Bread and eggs were distributed before the evacuation began, and some clutched their food while others ate in the midst of a stench of filth and death.

Just off Ashkenazi Square I walked into a ground-floor room of an old house and found it converted into a makeshift hospital where wounded men were lined up like sardines. In another room I found three corpses. They lay wrapped in sheets, in the dim light of small candles.

When we had first reached Ashkenazi Square, Peter had made straight for the group of prisoners. He looked them over and finally exclaimed, ”Well, there you are.” He was eyeing a man in a balaclava the way a cat does a canary.

“There’s the bastard,” he announced.

The man in the balaclava looked anxiously to me. “Sir,” he said in a soft voice which made me feel like I was listening to a valet in some English mansion,” I didn’t mean to desert, really I didn’t, sir. I got a bit squiffy one night, and when I sobered up I found I was here, and I couldn’t get back, sir.” Peter grinned. “I think they plan to shoot me, sir, and I didn’t really mean to desert.” Peter grinned again.

I drew Abdullah Tell’s attention to the Englishman by asking what would happen to him. Major Tell assured me he would be treated like the other prisoners of war. They were to be transferred that night to an internment camp in Transjordan.

After the fighters had been marched off, the time came for the civilians to be evacuated. Picking up their bundles, and stooping under the weight, they shuffled forward. Soon men, women and children lost their identity in a flow of bobbing heads and bundles. Dr. de Azcarate stood erect, his hands behind his back, watching them slowly file past.

“Misery always wears the same look,” I said to him.

He nodded, his eyes red. “I’m a Spanish republican,” he said, “and it was just like this at Malaga during the civil war.”

Cries were heard as the Arab civilians, disregarding the curfew, came leaping over rooftops into the Ashkenazi quarter. They hauled mattresses into the courtyards and ripped them open looking for gold. White down fluttered in the air and it soon looked as if it were snowing beneath the blue sky of Jerusalem. In their frenzy the Arabs started fires. Black smoke billowed out of windows while bright yellow flames licked up to the wooden balconies. The whole Jewish quarter was soon on fire, and as the Arabs plundered the smell of burnt flesh filled the air. When the flames were spent, what remained in the Ashkenazi quarter were the charred bones of the dead, a child’s two feet in half-calcinated boots sticking out from under a door placed over the body like a shroud.

Amman’s first intimation that war was not all rejoicing came in the shape of an air raid one morning at dawn. Though it killed only four bakers who were busy making bread, it left King Ab fearful and annoyed, pacing his palace and complaining bitterly that the Jews were trying to kill his father’s son.

The raid caused an acute case of spyitist. With no Jews available, the blame fell on the Palestinian Arab refugees. Three hundred and forty were picked up. Several people caught pointing were arrested and detained for questioning. That morning I received a visit from one of the Grand Mufti’s bodyguards. This man wore an Astrakhan cap on the back of his head and had the habit of cracking his knuckles.

“Some people talk too much,” he said. “Take Peter, the things he says.” The bodyguard rolled his eyes and cracked his knuckles. “Why don’t you give Peter a little advice, and tell him that writing is even more unhealthy than talking?”

I never had the chance, because I never saw Peter again. Like the English deserter taken prisoner in the Jewish quarter, Peter disappeared completely and totally, without leaving any trace.