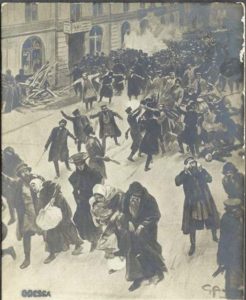

March 28, 1871, Odessa

Disorder broke out during Holy Week, on March 28, and lasted until April 1.

The official account of the Pogrom is detailed in reports by Governor-General of New Russia, P.E. Kotsebu, to the ministry of the interior. On March 30 1871, Kotsebu reported that the events were an outgrowth of the traditional fights between Jews and Greeks during Holy Week. The disturbances were expanded when the Greeks were joined by the Russians motivated by religious antipathy. The following day, Kotsebu noted that the fights were an annual occurrence, but were usually suppressed with ease. The entry of Russians into the fray complicated police procedures. Why had Russians joined in? “Recent events revealed that the religious antipathy of the Christians was joined to bitterness born of the exploitation of their work by Jews and the ability of the latter to enrich themselves and manipulate all matter of trade and commercial activity. In the crowds of Christians there were often heard the words ‘the Jews offended our Christ, they grow rich and they suck our blood.”

In another context Kotsebu complained to Petersburg about the role of the press, complaints that precisely foreshadowed bureaucratic altitudes in 1881–2-

“In the Petersburg and Moscow newspapers there continues to appear correspondence about the disorders which took place in Odessa, filled with exaggerated or completely false news. Such correspondence is sent to foreign newspapers. In large part it is written by Jews, with the objective of influencing public opinion everywhere for the assistance of the suffering Jewish community in Odessa.

If our capital newspapers eagerly open their columns to such correspondence, not even knowing the authors, then it meets an even more joyful reception in the foreign press, for this press is found almost everywhere in the hands of Jews or employs their participation as the closest of collaborators.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 21, 23.

April 10, 1871

Golos Newspaper critical comment on an article in the Odesskii vestnik which praised “all the diverse and timely measures taken by the higher authorities” in response to the pogrom-

“It’s true that these measures were diverse- they whipped, they arrested, they stabbed with bayonets, they butted with rifles, they lashed with the knout and the nagaika… All this is diversity to the extreme; as pertains to “timeliness,” I beg to differ with the opinion of the author of the article in Odesskii vestnik… First there was no action taken at all and then suddenly troops, Cossacks and artillery. This is one of many examples of how they react to street fights. At first they pay them no attention and then suddenly they require birch rods, artillery and Cossacks by the hundreds along with several army regiments.”

Source- Golos, April 10, 1871.

1881

The Pale of Settlement, where most Russian Jews were obliged to live by law, comprised 15 provinces in the northwestern and Southwestern regions of European Russia (Belorussia, Lithuania, the Ukraine, Bessarabia and New Russia).The number of Jews in the entire Russian Empire was reckoned at 4,086,650 or 4.2% of the population. Of these, 1,010,378 were in the Kingdom of Poland, not covered by the legal regulations of Pale. Polish Jewry constituted 13.8% of the total population. Within the Pale itself, Jews numbered 2,912,165 or 12.5% of the population. Of these, 2,331,880 or just over 80%, lived in towns or Shtetlekh, while 580,285 resided in the countryside or peasant villages. Only a miniscule number of Jews, 53,574 or .1% of the population, lived in the interior provinces of Russia.

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 5.

March 1, 1881

A band of revolutionary terrorists assassinated Tsar Alexander II. Rumors connected the Jews to the murder. Accusations against the Jews were made by the press. In Odessa, and elsewhere in the Pale of Settlements, there were predictions of a pogrom against the Jews.

April 1881

For most Jewish revolutionaries such an “enlightening experience” was not readily available, nor indeed necessary, to raise grave doubts about the wisdom of supporting the pogroms. Less drastic, but in the long run equally effective, in changing their attitude was their growing awareness that the pogroms were directed against the impoverished Jewish masses as an ethno-religious group, rather than as a social class of exploiters. A good example of this process of recognition relates to the pro-pogrom proclamation which Isaak Gurvich had prepared on behalf of the Jewish Chernoperedeltsy and Narodovoltsy in Minsk. Commenting on this affair, Gurvich reminisced-

“Well, I wrote this proclamation in which… I called on the peasants of the Vilna, Minsk, and Mogilev provinces to rise up against landowners and innkeepers. I gave the proclamation to Grinfest [printer of the Chernyi Peredel press in Minsk]. Several days later I met him again and asked what he thought of my proclamation. He told me rather nicely that it had been decided not to print the proclamation because of its appeal [to the peasants] to beat land-and-tavern owners alike. “Who are those innkeepers in the villages? Aren’t they all Jewish paupers?” – he asked me. I agreed with him… Perhaps, you might say that it was class instinct which spoke in him- his father owned a tavern… He knew from experience that the poor Jewish innkeeper of that time had nothing in common with the rich gentile innkeeper of central Russia who was the owner of the whole village.”

Getsov, one of the printers of the Minsk press, noted-

“The article was written in an agitational tone, viewing the pogroms as the beginning of revolution. [It] encouraged the people to continue, and to move on against the police and landowners. On us, the typesetters, this article had a repulsive effect. Unanimously, we decided not to print it.

However, it was necessary to bring its author to reason… This mission was entrusted to me. With the article in my pocket I hurried to St. Petersburg. To Zagorskii’s [the author’s] credit it must be said that I had no difficulty convincing him that these pogroms were not a class movement, but were based on superstition, prejudices, misunderstandings, etc., that its victims were in general as impoverished and proletarian as the pogromshchiki themselves; that this was the doing of the government agents to fight the revolution and also of capitalist exploiters [resenting Jewish competition]. Zagorskii listened to me without objections, destroyed the article and immediately wrote another, completely different in spirit. Triumphantly, I returned [to Minsk] by the next train… I was happy and my comrades were delighted.

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. pp. 113-114.

April-June 1881

On 8 April 1881, a secret circular from Minister of lnternal Affairs M. T. Loris-Melikov empowered all governors “in extreme cases, where it seems drunkenness could lead to disorders” to close down drinking establishments. As justification for this extraordinary measure, Loris-Melikov cited the “current alarming events (pogroms),” which made “the prevention and suppression of any disorders the special concern of the police authorities…

After receiving this directive, P. P. Albedynskii, the Governor General of Warsaw, deluged his governors with circulars of his own. On 27 April, he wrote to them-

“It has come to my attention that in certain localities of this region, a rumor is circulating among the lower classes that the Jews are expecting the advent of the Messiah and that attacks on them are expected…

At the present time, one of the homeowners in the city of Warsaw has received an anonymous warning about dangers which allegedly threaten the local Jewish population.

In view of the confrontations which have recently taken place in some southern [Ukrainian] cities between the Christian and Jewish populations, I most humbly beg Your Excellency to take appropriate measures to strengthen surveillance in order to prevent anything similar in the province entrusted to you.”

On 16 June a relieved but still concerned Albedynskii conveyed the following message-

“The holidays passed quietly but it is nevertheless impossible to be completely sure that the future is secure. The peasants, with the onset of the busiest period of the season, will naturally devote themselves to their work and will avoid any excitement on the side. But the same cannot be said for factory workers who are most susceptible and inclined to passions…

Strict surveillance of the [popular] state of mind at this critical time constitutes the object of my special concern. Therefore, I ask you not to weaken vigilance.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 167.

April 21, 1882

Akselrod felt that the pogroms demanded a fresh look at the Jewish Question and the role of Jewish revolutionaries in the movement. Under the influence of Gurevich, he seriously considered including in his brochure the idea of emigration to Palestine for Jews persecuted in Russia. This reasoning was not well received by Deich who, speaking on behalf of the Geneva Chernoperedeltsy, declared-

“We, as socialist-internationalists, should not at all recognize special obligations toward” co-nationals” [soplemenniki] … Of course, we do not say “that one ought to remain indifferent… But our approach to the [Jewish] problem must be based on a universal-socialist standpoint that seeks to fuse nationalities instead of isolating one nationality [the Jews] still more than is already the case. Therefore… do not advise them to move to Palestine where they will only become still further frozen in their prejudices… If they are to emigrate- then [let them go] to America where they will merge with the local population.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. pp. 118-119.

1897

Jewish workers found, the General Jewish Worker’s Party of Russia and Poland, the Bund.

Jewish laborers now had their own political party in order to represent both specific and general interests within the context of the Russian revolutionary movement. Delivering a key address at the founding meeting of the Bund, Arkadi Kremer outlined the priorities of the new organization-

“A general union of all Jewish socialists will have as its goal not only the struggle for general Russian political demands; it will also have the special task of defending the specific interests of the Jewish workers, carry on the struggle for their civic rights and above all combat the discriminatory anti-Jewish laws.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 151.

1905

Odessa Pogrom

Evidence exists that during the 1905 pogrom in Odessa, the army supported the mob-

The Bolshevik Piatnitsky who was in Odessa at the time recalls what happened-

“There I saw the following scene- a gang of young men, between 25 and 20 years old, among whom there were plain-clothes policemen and members of the Okhrana, were rounding up anyone who looked like a Jew—men, women and children—stripping them naked and beating them mercilessly… We immediately organized a group of revolutionaries armed with revolvers… we ran up to them and fired at them. They ran away. But suddenly between us and the pogromists there appeared a solid wall of soldiers, armed to the teeth and facing us. We retreated. The soldiers went away, and the pogromists came out again. This happened a few times. It became clear to us that the pogromists were acting together with the military.”

Source- Alan Woods. Bolshevism- The Road to Revolution. Part Two- The First Russian Revolution

By the end of the Odessa Pogrom 800 Jews were dead, 5,000 wounded, 463 children orphaned and 10,000 families ruined, property destruction was estimated at more than 100 million roubles.

An emergency telegram sent by the Odessa Aid Committee to the Alliance Israelite, a Paris relief organization read

“The massacres at Odessa surpassed the cruelties of the rest of the world… 10,000 families without bread or roof- Indescribable miseries- Immediate aid needed on a large scale- Urgent!”

Tsar Nicholas II in a letter to his mother the Dowager Empress expressed the belief that the way to short circuit the revolution was by attacking Jews-

“In the first days of the Manifesto the subversive elements raised their heads but a strong reaction set in quickly and a whole mass of loyal people suddenly made their power felt… the revolutionaries had angered people once more; and because nine-tenths of the troublemakers are Jews, the People’s whole anger turned against them. That’s how the pogroms happened. It is amazing how they took place simultaneously in the towns of Russia”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. pp. 233-234.

January 1906

Count Lamzdorf to Tsar Nicholas II

“There is thus no room for doubt as to the close connection of the Russian revolution with the Jewish question in general… Nor can it be denied that the practical direction of the Russian revolutionary movement is in the Jewish hands…it is precisely the Jews who are standing at the head of revolutionary movement.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 222.

October 1905-1906

Propaganda

A. A. Lopukhin, Director of the Department of Police reported to Witte that during October and November 1905, a secret printing press located at Police headquarters in St. Petersburg printed thousands of anti-Semitic pamphlets, which said-

“Do you know brethren, workmen and peasants, who is the chief author of all of our misfortunes? Do you know that the Jews of the whole world… have entered into an alliance and decided to completely ruin Russia. Whenever those betrayers of Christ come near you, tear them to pieces, kill them.”

A May 17, 1906 Duma report stated that

“Official documents… show that the Department of State Police was directly concerned in the mission of inflaming one section of people against the other, a mission that has concentrated hordes of assassins in the midst of peaceable citizens… proclamations drawn up by the same Department, incited the populace to massacre persons of other religions… ”

When Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte learned that individuals were using facilities at the Ministry of Interior to print anti-Semitic pamphlets he ordered that “the printing of the proclamations be immediately stopped. His order was ignored and the publications by members of the Okhrana, under the charge of General Trepov continued. Lopukhin’s statement to the Duma clearly indicates the schism within the government-

“When in January and February I was collecting data relating to the organization of pogroms, I never encountered any member of the political or ordinary police who was not imbued with the absolute conviction that there are in fact two governments… one in the person of Secretary of State Count Witte, the other in the person of General Trepov who according to universal conviction, lays before the Tsar reports that represent the situation in the country in a different light from that in which it is represented by Count Witte, and thus exercises an influence on the direction of policy… This conviction is as firm as the belief that General Trepov is in sympathy with the pogrom policy”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. pp. 235-236.

September 1906

Reports from Sedlits, in Poland, indicate that a pogrom was organized by local officials and members of the Monarchist League. During the pogrom 100 Jews were killed and 300 wounded. A telegram from Warsaw on the pogrom stated-

“Evidence of the prearrangement of the pogrom at Sedlits by local authorities and the Monarchist League is accumulating… when the massacre was being planned, the officers of the Ostrolensky Regiment declared that they would maintain order and fire upon the rioters. The regiment was removed from the town and its place was taken by the Libau Regiment, which distinguished itself so unenviably at Belostok.”

Source- Klier, John D. and Lambroza, Shlomo. Pogroms, Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press 1922. p. 238.