Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism Video Transcripts

Video 1 – Kabbalah in Safed in the 16th Century

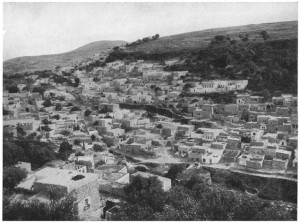

In the wake of the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 15th century, Safed, a town in northern Israel became a major center both and economically speaking and religiously speaking. Within a relatively short span of time one finds in this small city a cluster of kabbalists of a very impressive pedigree. Amongst them is Joseph Karo, better known as the author of the Shulhan Arukh, a mjor legal code, as well as Moshe Alsheikh, Solomon Alkabezt, and his Student, Moses Cordevero. One of the distinctive features of Kabbalistic activity in the 16th century is the recording of personal visions, which was a rather rare phenomenon in earlier kabbalistic sources. Joseph Caro is perhaps the best example of this, and his major kabbalistic work is the Maggid Meisharim, a book that records the visions of the divine that he received from his maggid who was his spiritual mentor who is also identifies as the Shekhinah – the divine presence. Interestingly enough, these visions are connected to the sections of the Torah, which is related to a larger feature of the kabbalsitic temperament, going back to the earlier Middle Ages, where exegesis, or the study of text itself was understood as the vehicle to have visionary experience of the divine, based on the kabbalistic identification of the Torah and the Divine Name.

During the 16th century was also fine an effort, especially on the part of Cordevero, to systematize the earlier kabbalistic works, so in a number of his treatises, but perhaps most importantly in his Pardes Rimmonim we find a systematic presentation of Kabbalah whose scope was unparalleled in previous sources. All of the contradictions, or conflicts, different view points, are presented by Cordevero, who attempts to render them harmonious in a grand scheme, and this does prepare the ground for the next major development attributed to the Ari – Isaac Luria.

We also find an intensive activity in the circle of kabbalistis of Safed in the 16th century dedicated to the study of the Zohar, the writing of commentaries on the Zohar, and perhaps most importantly, an effort to redact the text into publishable form. The Zohar was published between 1556-1558 for the first time in Mantua and Cremona, two cities in Italy, but the work of editing and redaction was carried out by kabbalistis in Safed, who had the manuscripts that they then sent back to Italy. It has become increasingly clear that this act of redaction and editing was far more aggressive than we thought previously. That is to say that they weren’t simply copying the text of the Zohar, but they had a great hand in shaping the literary form of the text, and the way that it was eventually published, which then influenced subsequent generations of readers of the Zoharic text.

Video 2 – Abraham Abulafia

Abraham Abulafia was a Spanish Kabbalist from the 13th century who was responsible for developing a special kabbalistic path which he referred to as kabbalah nevuit – “prophetic Kabbalah” – sometimes referred to in the scholarship as the “ecstatic Kabbalah,” because the emphasis is placed on attaining a state of ecstatic union with the divine, which Abulafia understood, following Maimonides, to be the spiritual meaning of prophecy. For Abulafia the means by which one achieves the state of prophetic illumination or conjunction with the Divine is through letter combination – tzeruf ha-ottiyot – which breaks down actually into three different stanges, beginning with writing, then progressing to verbalizing the permutation, and then finally practicing these combinations or permutations in the mind without either writing or verbally articulating them. The purpose of the letter combination according to Abulaifia, is to disentangle the soul from its imprisonment or the knots of the body, so that it in fact can be conjoined with the Divine. For Abulafia, the ultimate reality of the Divine is the four letter name, the Tetragrammaton, which he understood as well as the basic stuff of all reality, so that the physical or material cosmos according to Abulafia, could be transformed in the mind of the mystic into this semiotic reality, being part of the letters that are part of the divine name. The ultimate goal for him is for the individual to become angelic, which means to obtain the higher state of consciousness, to be incorporated into the Name, or to receive the divine light. This for him is prophecy, but it is also understood by him in messianic terms, so even though he uses the traditional language of the Messiah, it is clear that what Abulafia had in mind was a spiritual state, rather than something geopolitical. Messianism for him meant attaining a state of consciousness where the individual is no longer separate from its divine source, but is incorporated back into the Name, and in that sense becomes angelic or divine.

Video 3 – Hasidei Ashkenaz

Hasidei Ashkenaz refers to a group of pietists who were active in the Rhineland in the 12th and the 13th centuries. Tracing their lineage back to a family that had emigrated from Palestine to southern Italy in the 9th century and then were forced to leave Italy in the 10th century and relocated in the Rhineland . The principle group of Hasidei Ashkenaz was headed by Samuel the Pious, followed by his son Judah the pious, and then followed by Eleazar of Worms. All the evidence seems to point to the fact that early on most of the mystical doctrines that informed this group were transmitted orally or put down in very abbreviated fashion, in what in rabbinic terms would be called roshei perakim, “chapter headings.” The major work of the group is called Sefer Hasidim, “The Book of Pious,” which consists of different parts, some of them going back to Samuel the Pious, some of them reflecting later interpolations based on the work of Eleazar of Worms, but the bulk of it attributed to Judah the Pious. A shift in orientation occurs between Judah the Pious and Eleazar of Worms. Judah the Pious continued the orientation of Samuel his Father and saw the ideal of pietism as something to be limited to an isolated few, whereas Eleazar changed his orientation to some degree and saw that certain dimensions of the pietistic teaching could be disseminated and adopted by greater numbers of Jews in his time, although even Eleazar maintained some degree of restriction about the secrets, which he thought too were limited to only a small group of individuals. As far as the history of Jewish Mysticism is concerned, Hasidei Ashkenaz are important because they did cultivate esoteric secret traditions that in part go back to the Chariot mysticism of Talmudic times, the heichalot texts, and in fact much of our manuscripts that preserve this material were copied by Hasidei Ashkenaz or were based on copies of their copies, so we are indebted to them for preserving this material. But in addition to preserving the material, they seem to have cultivated ascent experiences like those described in these works. The principle feature of their mystical piety was the seeing of the divine Glory, which came about through the transmission of the divine Name – the most sacred of the divine Names, the Tetragrammaton, the four letter name. The Pietists believed that the four letter name takes on the form of light, which becomes visible through the imagination, and they also believed that that light was embodied in the scroll of the Torah, an idea that they based on the identification of the Torah and the Name, a doctrine that we find in a number of authors beginning in the 12th century and including later kabbalists.

The Pietists maintained on a more public level that the nature of God should be purified of all anthropomorphic representation, and in this regard they were influenced by philosophical works, including Saadia Gaon, and parts of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah, but in a more secret sense they cultivated a portrait of God that was heavily anthropomorphic, and utilized the older texts, the Heichalot texts and the Shiur Komah texts, which describe God’s dimensions in great detail, as the basis of their own mystical piety. The way to achieve these extraordinary experiences of seeing the Presence or receiving the Name was through intense ascetic renunciation of physical pleasure. Particularly, great emphasis is placed on sexual asceticism, and this has to do with the fact that they viewed the inner workings of the Divine in terms of sexual symbolism, and they viewed the relation of the individual to the Divine as well in intensely erotic terms, so in order to have these experiences of the divine or to gain the inner knowledge of the workings of the Divine, it was necessary for an individual to refrain from sexual behavior beyond the requirements of Jewish Law.

Video 4 – Evil in Kabbalah

The kabbalists, like others, have struggled with the question of evil, and how we are to understand both moral and natural evils in the world. At some point there begins to develop a rather unique approach to this old problem, and the kabbalists understand evil to be an aspect of the Divine, that attains some kind of independent status from the Divine. So for instance, in the Bahir there is a reference to the “left hand” of God. In time the kabbalists cunderstood that left-handedness of God to be connected more specifically with the attribute of Judgement, or limitation, constriction, so that evil was understood by them to be this quality of limitation unbalanced, or un-tempered by divine grace, divine love.

Eventually, by the latter part of the 13th century in Castile the kabbalists started to develop a whole mythology around the evil side of the Divine, and that the quality of Din produces emanations that are in conflict with or struggle against the holy forces of the divine. And just as the holy forces are constituted by a male and a female, similarly the realm of evil powers or demonic is constituted by a male and a female, eventually identified as Samael and Lilith. But in comparison to the holy side, the sinister side is again referred to as the left which is struggling against the right. This doctrine receives a specific name in the Zohar –sitra ahra – which literally means “the other side.” Philosophically speaking, since the Divine comprises everything, there can’t be an other that is ultimately other, so otherness has to be understood in a relative way, because there is ultimately only one source of all that is. Light and dark both derive from the same one source, namely, the Infinite.

Within the tradition there is a tension or conflict between two different approaches to evil that reflect this very philosophical issue. Sometimes evil is described as being obliterated at the end of time. But on other occasions the model that is used is re-integration or containment of the evil, a restoration of the dark back into the light whence it came forth. Logically the latter model of integration is more consistent with the view that there is ultimately only one force or one power, but there is no question that whether one understands this in a more dualistic or more monisitic way, much attention is given by the kabbalists to the struggle between the force of evil and the force of good. They understood history as an unfolding of this struggle, and that ritual behavior was the means by which one kept the evil at bay, or kept it separate from the good, and kept the unholy out of the precinct of the holy, whereas transgressive behavior allowed for a confusion of boundaries, and allowed the evil to penetrate into the good, and that would be reflected in the sufferings experienced below in the historical arena. The ultimate task, again, would be either to obliterate the evil, or to re-integrate it back into the good, and that would signify the restored unity and wholeness of the Divine that would mark the messianic redemption at the end of time.

Video 5 – Isaac Luria- The ARI

Isaac Luria, better known as the Ari or the Ari ha-Kadosh “The Holy Lion,” an acronym that refers to his name, Rabbi Isaac, was a mojor figure on the scene in Safed in the 16th century. He was born in Jerusalem, and after his father died his mother moved with him to Egypt, where he was raised by his uncle, a famous Talmud scholar, Bezallel Ashkenazi. While in Egypt he started to study Kabbalah with David ibn Zimra, The Radbaz, and eventually made his way to Safed to join up with kabbalists who were already there, including Cordevero, and Hayyim Vital. It is clear though he was only in Safed a short period of time – he died a young man – that he had a major impact on the scene there and changed the way of thinking of major kabbalists like Haim Vital, who in his early stages of development followed the approach of Cordevero, but eventually becaome the most important disciple of Isaac Luria.

Luria wrote very little himself. He is the author of three very famous poems for the three traditional meals on the Sabbath. In addition he left behind some manuscripts that had commentaries on parts of the Zohar, which were eventually published by his students, but for the most part his teachings were disseminated orally to a small circle of followers and desciples. One of the distinctive features of Luria’s Kabbalah was that each of the disciples was accorded the priveledge to interpret it in the way that he understood.

One of the most important shifts in Lurianic Kabbalah was placing great emphasis on Tzimtzum, the contraction or the withdrawal of the Divine as the beginning of the process of emanation. This is an utterly paradoxical idea, which is explained philosophically by Hayim Vital, to answer the question how can there be room for anything that exists, if the infinite light comprehends all reality. So in order to make room for there to be an existence other than the infinite light, there had to be a contraction or withdrawal of that light into itself to create a space devoid of that light. According to some other disciples, primarily Joseph ibn Tabul, the secret of contraction had to do with purging the Divine of the roots for evil, or the aspect of unbalanced judgment the Divine, so this is a process of catharsis through which God rids God’s self of the unwarranted refuse, in order for there to be a process of emanation. But in the unfolding of this emanative process, this purging of evil has to occur at different levels. The process that is most important for understanding Lurianic Kabbalah in terms of its impact on understanding human existence is with the creation of Adam and the transgression of Adam and Eve, there is a re-fractiuring of the Divine, so that there is a cataclysm within the Divine, and the shells are broken into pieces, and attached to those shards of the vessels that are broken are sparks of light, and it becomes the task to libertate those sparks of light and restore them to the Infininte. History is understood primarily as the unfolding of this process, so that the messianic redemption will occur when the final sparks are restored back into the Godhead and the original sense of unity is re-achieved.

Lurianic Kabbalah also, despite its complexity, is to be noted for the influence that it had on changing the nature in Jewish ritual, so that for the first time we find practiced betraying influence of kabbalistic ideas, such as the institution of the kabbalat Shabbat prayer on Friday evening, and this afforded the opportunity for the Kabbalah to become more of a social force in Jewish societies, even though the ultimate meaning of these ritual changes might not have been readily discerned. But precisely because the changes were effected in ritual behavior, you have an example of how the mystical doctrine becomes more popular and influential.

Video 6 – Moses de Leon

Moses de Leon was a kabbalist from Castile who was born in 1240 and died around 1304. He is best known for his involvement with the Sefer ha-Zohar, “The Book of Splendor.” The whisper of Moses de Leon being somehow involved with the writing and dissemination of the Zohar can be traced back in time really to the end of the 13th and early part of the 14th century. The earliest attempts at dealing with the Zohar in some kind of critical way, for instance in the 17th century by Jacob Emden, reveal that Moses de Leon was considered to have played an integral role. This view was reaffirmed on stronger textual and philological ground in the 19th century, principally in the work of the German-Jewish scholar Adolph Jellinek, and it was accepted by Heinrich Graetz, and then in the 20th century by Gershom Scholem, although at first Scholem resisted this idea, but in time came to accept it, and it became the paramount view that has informed scholarship – that Moses de Leon was responsible for the chief part of the Zohar, written in Aramaic, and attributed to Shimon ben Yochai and his colleagues. Part of the argument was based on a careful comparison of the Zoharic text with Hebrew works of a kabbalistic nature written by Moses de Leon.

More recently there has been something of a paradigm shift away from seeing Moses de Leon as the sole authorship of the bulk of the Zohar, and to see him rather as part of a fraternity or a group that congregated in Castile and who’s views were reflected in the imaginary personalities of the Zohar. This is yet to be proven, but it is a suggestive thesis. And even if it proves to bear fruit, the role of Moses de Leon still remains extremely important, and it does seem to be that he was most likely the secretary of this group, as it were, or the principle Kabbalist responsible for the writing down of these secrets and the eventual dissemination of the text.

Video 7 – Mysticism and Mystical Experience

There has been much scholarly discussion regarding these terms, and in fact there is no real consensus as to what mysticism means, but there have been two dominant schools of thought regarding the nature of mysticism. One is known as the essentialist school, and the other the contextualist. The essentialist view is that there is something identifiable regarding the nature of mysticism and mystical experience, and we can chart out the characteristics that would constitute that phenomenon, and we can find it cross-culturally in different religious and spiritual contexts. The contextualist argument would be more skeptical about the possibility of identifying a characteristic or even a series of characteristics that would be found in different religious and spiritual paths across time and in different geographical regions.

If one were to take those two views in the extreme, then there would be a kind of paralysis, intellectually speaking. So it seems that it is more beneficial to adopt something of a position in between those extremes, which affirms both of them at the same time, without collapsing one into the other or choosing one over the other. When we apply that specifically to the history of Jewish mysticism, I think that it is again fair to say that there are some features that we find in these texts that are both common through the course of Jewish history and also shared by other religious traditions, although the particular way that these characteristics would be expressed in the history of Judaism in different historical periods and geographical regions will vary. If I had to choose two of the most important features that I would identify as mystical, they would be vision and union. Again I don’t suggest that these are absolutely separate, but I think that we can make a distinction between the two.

Some Jewish mystics have placed the vision of the Divine as the primary concern, and there are practices that are cultivated specifically to achieve that result. Whereas other mystics have placed more emphasis on the unitive experience, so that the vision would be a lower form of achievement, whereas the true goal and aspiration of the mystical path is to overcome the sense of difference and be reincorporated into the Divine. Typically for the kabbalsits, that reincorporation into the Divine is expressed in two primary ways; either as being incorporated into the Name – the Tetragrammaton – which is believed to be the potency of the Divine, but also the underlying reality of all that exists, that is to say that all that is, is but a manifestation of that ineffable Name. Or, they understand this experience to be restoration into the light that filters through the chain of being from the divine emanations down into this material world.

These in my mind are two different ways to articulate the same experience, which we could call the ultimate experience, which overcomes the sense of difference between the individual and the ultimate reality, that is, the Divine essence, which is an essence that ultimately is unavailable to human knowledge – it’s an inessential essence in a sense that we can never know what it is, but only how it manifests itself though its concomitant revelation and concealment.

Video 8 – Erotic Symbolism in Kabbalah

The kabbalistic tradition, along with other mystical cultures, puts great emphasis on the sexual, in its effort to both describe the nature of God, and also to describe the nature of the mystic in his relationship to God. For the kabbalists, the mystery of Eros is referred to early on as “the secret of the androgyne,” (the sod du-partzufim). Because of their belief that just as the human below was created male and female, so the image of the human above, which is the Divine, is constituted by both a masculine and feminine dimension.

More specifically for the Kabbalists, the masculine dimension is the potency to overflow, or the attribute of Hesed, Divine Grace, whereas the feminine attribute, or the feminine dimension, is the capacity to receive, or the attribute of Din, Judgment. The ultimate secret of Eros, or the mystery of Eros, refers to the secret of pairing together those two aspects of the Divine, maintaining the unity between the potential to overflow and the capacity to receive.

Transgression, sinful behavior, exile, is understood by the kabbalists as creating a fissure, or a rupture, a separation within the Divine, between these two aspects. Following closely the biblical accounts of creation, for the kabbalists, the ultimate unification consists of restoring the element of the male androgyne that was separated from Him in the form of the female, so that the pairing is not understood to be a kind of endless process, but it serves as a goal, ultimately, to restore that part of the divine that was severed, and to thereby reconstitute the mystery of the androgyne, which is the ultimate secret of Eros.

Video 9 – Prayer and Worship according to Kabbalah

Again as we find in many mystical traditions, so we find in the case of the kabbalists, great emphasis placed on prayer, both the actual ritual of prayer, and speculation as the mystical meaning of prayer. For the kabbalists, beginning in the 12th century, prayer ultimately became the primary means by which the individual is conjoined to the divine. Sometimes this conjunction is described as the cleaving of the human thought to the Divine thought, and sometimes it is expressed as the conjunction of the will, the human will that is finite, with the Infinite Will, or the Will of the Infinite. So prayer, as its biblical precedent in sacrifices, was seen as a primary means by which one could attain this contemplative ideal of union or conjunction with the divine, the means by which an individual overcomes his own finitude, his own sense of limitation, and merges with or is integrated into the infinite will of the Divine that extends all the way beyond into the Infinite.

Video 10 – Mysticism and Secrecy in Rabbinic Literature

If we understand the word mysticism to refer to some type of experience of immediacy with the Divine, then it is appropriate to speak of the rabbinic corpus in the way that Max Keddushin did; a kind of “normative mysticism,” by which he meant that that Rabbis cultivated the idea that through the study of Torah and the performance of ceremonial ritual, one comes to live in the presence of God. There is no evidence in the Rabbinic corpus for Rabbis cultivating extraordinary experiences, or practices to have experiences of a mystical nature – whether union or vision of God – but there is evidence in the rabbinic material that certain subjects were considered by the rabbis to be too sensitive to divulge to the masses.

In particular, the Rabbis distinguished three subject matters that they considered to be secretive in this way- the arayot, illicit sexual relations, ma’aseh bereishit, the account of creation, and ma’aseh merkavah, that account of the chariot. Each of these disciplines is connected in the Rabbinic imagination with a particular part of the biblical text. The illicit sexual relations – arayot – are connected to the eighteenth chapter of Leviticus; Ma’aseh Bereishit, the account of creation, to the first chapter in Genesis; and Ma’aseh Merkevah, the account of the chariot, to the first and tenth chapters of Ezekiel.

These were viewed in ascending order as being more esoteric, and in the course of time this notion of subject matters that were to be held from public dissemination had a profound impact on the sensibility cultivated by kabbalists in the Middle Ages, who placed a primary emphasis on the notion of secrecy, and often expressed that in terms of the language of the Rabbinc categories.

Video 11 – Secrecy, Mystery and Esotericism in Jewish Mysticism

There is probably no one word that best captures the worldview of the kabbalists as the word “secret,” or “mystery, or “esotericism.” The emphasis placed on secrecy is something that the kabbalists inherited from the Rabbis, and perhaps goes further back to a kind of apocalyptic sensibility about the mystery of the divine to be revealed at the end of time.

For the kabbalists in the Middle Ages, secrecy has primarily two implications. The first is the idea that these matters of a sensitive nature about God, the soul, or the world, should only be divulged to one who is a worthy recipient. The second meaning of the secret, however, involves the ultimate impenetrability of the secret, so that even the master of the esoteric wisdom, the adept or the kabbalist, would never fully claim to comprehend the mystery, and that the comprehension of the mystery ultimately lies in its incomprehensibility, in its illusive character, and in its ability to constantly repeat itself as the secret that is revealed as the secret that can never be revealed.

Video 12 – Sefer ha-Bahir- The Book of Illumination

Sefer ha-Bahir- The Book of Illumination, which can be described as a mystical midrash that has been attributed to Nehunia ben ha-Kana, a rabbi who lived in second century Palestine. The book is an anthology of statements. There are not one but various competing systems of thought in the Bahir, which seems in all likelihood to have been redacted in the form that we have it in the 12th century Provence, and it is first cited as a work in 13th century kabbalistic literature. Irrespective of the probability that there are different competing ways of describing God, the subsequent history of the way the text was read is such that it was thought to be promoting the doctrine of the Divine made up of up ten powers, or ten potencies, the sefirot, but also identified by the Rabbinic notion of the ten “sayings” by means of which the world was created.

Perhaps most importantly in the Bahir is the emphasis placed on viewing the Divine as being both male and female, and understanding that the unity of the Godhead consisted of the pairing, the conjunction, of these two different aspects; what later kabbalists would refer to as the “secret of the androgyne,” the sod du-partzufim. This stands in striking contrast, for instance, to the view of the divine unity that was being promoted at the same time by a figure like Maimonides, who would have understood God’s unity as being a simplicity that denies any possibility of parts – bodily parts or attributes, so that the kabbalisitc idea promoted by the Bahir and subsequent kabbalists, strikingly opposes this view and understands the unity in a more dynamic and organic fashion, and primarily related to the sexual implications of the Divine pair, male and female.

Also highly important was the fact that the bahiric authors or the redactors of the bahiric text – kabbalists in Provence – attached this emphasis on the erotic and sexual symbolism of the Divine to the Rabbinic ritual, so that for instance, Sabbath, was understood in its very constitution as being representative of this holy union between the male and the female – the female being the eve of Sabbath, and the male being the day of Sabbath. Or, for instance, the phylacteries were understood as embodying the same secret; the arm phylacteries corresponding to the female, and the head phylacteries to the male. Or, for instance, the commandment to take a citron fruit and a palm branch on the festival of Tabernacles, Sukkoth, was again understood as a performance of the sacred union of the male and female aspect of the divine.

This combination of sexual symbolism and normative ritual, had a tremendous impact on the development of subsequent Kabbalah, running its course through history, even up until the very present.

Video 13 – Sefer Yetzirah- The Book of Formation

Sefer Yetzirah- The Book of Formation, is a work of cosmology and cosmogony – cosmology, the structure of the universe, and cosmogony, how the universe came to be. It appears that the work is made up of two discrete literary units. The first part identifies the agent of creation as the ten sefirot, and the second part identifies that agent of creation as the twenty two letters of the Hebrew alphabet. At some point in the redaction of the text, these two parts were brought together, through which the umbrella concept of the thirty two paths of wisdom came to be.

With respect to the second part, the idea of creation through the letters, we have other evidence of that, including in the rabbinic corpus. But with respect to the first part, the sefirot, this is the first time we have a reference to that exact term. It’s not entirely clear what the meaning of the term is in the context of Sefer Yetzirah, but it does seem to refer to either the depths of the cosmos or aspects that constitute the nature of the Divine, and these sefirot are described, paradoxically, as being ten in number, yet unlimited – midatan eser she-ein lahen sof – “their measure is ten which has no limit.” Later kabbalists understood, and I think probably correctly, that this in its original context was already meant to communicate this idea that while the sefirot are enumerated and hence limited, they are expressive of an unlimited power of the Divine. And even though there are ten, this isn’t an assault on the basic principle of Jewish monotheism, because as the text of Sefer Yetzirah already emphasizes, “their beginning is fixed in their end, and their end is fixed in their beginning,” so even though there is a multiplicity of potencies that make of the Divine, they constitute one organic unity, like the circle whose end and beginning are identical.

Video 14 – The Ten Sefirot

The term “sefirot” was first introduced by Sefer Yetzirah, the book of formation. It is difficult to know exactly what was intended by the authors of this text, and there is no single word in English, or any other language for that matter, that captures exactly what is intended by the “sefirot.” But, if we combine three different meanings, then we would come close to understanding the way that later kabbalists understood the term sefirot. That is, “sefirot” is derived from, safor, or lispor, or mispar, words that all intend something to do with counting or enumeration. It is also related to le-saper or sippur, “to tell” or “to narrate.” And finally, it is related to the word sapir – Sapphire, or “light,” “luminosity.”

For the Medieval Kabbalists the term sefirot refers to the aspects of the Divine that reveal the hidden Ein Sof, but do so by concealing that which they reveal. The sefirot are at the same time the enumerations of the infinite Divine; the narration of the Divine persona; and the illumination of the Divine darkness. For kabbalists, contemplation and engagement with the sefirot meant a kind of illuminative participation in the nature of the Divine, and this experience, again, is based on those three different meanings of the term sefirot. To know the sefirot one is participating in the enumeration of the Divine, the counting of the Infinite – and utterly paradoxical idea; one is also participating in the narration of the Divine myth, the story of the Divine; and finally, one is participating in the illumination of the Divine darkness, that is, the Ein Sof.

Video 15 – Shabbtai Zvi

Shabbtasi Zvi was a Jew from Turkey in the 17th century around whom a messianic movement, or a pseudo-messianic movement evolved in that century, and eventually began to have an impact on the Diaspora Jewish community at large, as well as the Jewish community within Palestine. The two principle exponents of the theology of Shabbtai Zvi, or what is known as Sabbatianism, are Nathan of Gaza, a kabbalist from Palestine, and Abraham Cardozo, a marrano Jew who returned to Judaism.

Shabbtai Zvi himself wrote little and probably was not the one responsible for explaining his messianic pretensions in the complicated kabbalistic manner that they were explained. The impact of Shabbtai Zvi should be seen through other channels, more popular forms of religious devotion, such as amulets and prayers. The messianism of Shabbtai Zvi was distinctive in that it was based on what are referred to as the ma’asim muzarim, the “strange acts,” acts of transgression that seemed to break the law, but are endowed with special messianic significance in that the breaking of the law was seen as the means to fulfill the law – a fulfillment that signified the fact that it was the messianic era. These transgressive or antinomian forms of behavior reached a crescendo of sorts in September of 1666 when Shabbtai Zvi reportedly was forced either to convert to Islam or suffer imprisonment, and he chose to convert. For his followers this was the ultimate sign, the ultimate plunge of the Messiah into the shells of the deomonic, to liberate the most difficult sparks of light to herald the final redemption. Some of his followers, who eventually become known as the Donmeh, followed his path and converted to Islam in emulation of the Messiah. Others rejected that approach, although they justified the apostasy of Shabbtai Svi himself. Later in the 18th century there arose Jacob Frank, who thoughts of himself as a kind of reincarnation of Shabbtai Zvi and emulated the apostasy, but in his case he converted to Catholicism rather than Islam.

What marked Shabbtai Zvi and the movement that surrounded him was this very unusual approach to messianism. And while it can be explained by historical factors unique to the 17th century, the fact is that the seeds for this approach are found in much older kabbalistic documents, and especially the later strata of the Zohar, which were reportedly the most favorite texts of Shabbtai Zvi himself. In these later strata, the Raya Mehemna and Tikkunei ha-Zohar, you find the idea expressed that there is a “Messianic Torah” or the “Torah of the Tree of Life” which stands in contrast to the Torah that now reigns, which is the “Torah from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil,” so that in the pre-messianic historical era it is necessary for the Torah to express itself through duality – through what is permissible and what is forbidden – whereas the messianic Torah or the “Torah of Emanation” is from the Tree of Life, which overcomes the duality between good and evil, between dark and light, between Israel and the nations. So while we have to understand Shabbtai Zvi and Sabbatianism in its historical context, it is also important to emphasize that philosophically speaking, this dimension is much older in the kabbalistic tradition.

Video 16 – The Secret Meaning of Jewish Laws and Rituals (Mitzvot)

Ta’amei ha-Mitzvot, “the reasons for the commandments,” is something that was treated in a very secretive way by the Rabbis in the Talmudic period. They were very reluctant to explain the reasons for the commandments. But in the Middle Ages this began to become a very important enterprise, in part due in fact to the rise of Karaism and the attack on Rabbanism, and the need to defend the Rabbinic understanding of ritual.

The kabbalists in the Middle Ages are part of this longer tradition, this effort to legitimate or philosophically explain and explicate the commandments. For the kabbalists, the role of the commandments assumes what is referred to in scholarship as a theurigcal role. That is to say, it is by means of the commandments or fulfillment of the commandments that one maintains the unity of the Godhead between the male and female dimensions, and also augments the power of the Divine. Some kabbalists explain this also in terms of the holding the sefirot in place, because the inclination of the sefirot is to go back up into the Infinite, and by performing the rituals with specific limbs, the “limbs” of the Divine shape are held into place.

Video 17 – Male and Female in Kabbalistic Symbolism

One of the distinctive features of the kabbalistic tradition is the emphasis it places on portraying God in male and female terms. The masculine dimension of God is understood to be the attribute of hesed, “grace,” the capacity to overflow, and the feminine dimension is thought to be the capacity to receive, or the attribute of din, “judgement.”

Already in the Bahir there is emphasis placed upon the sense of the feminine as being dislocated from the Divine, being exiled in the world, and the task for the mystic is to re-integrate that fallen aspect of the Divine, the feminine, back into the Godhead – to restore the spark of light back to its source. This served as the paradigm for the kabbalistic understanding of ritual and the mystical import of ritual. Through doing the proper deeds with the right intention one reunites the feminine with the masculine and in that way anticipates what the kabbalists understood to be the ultimate redemption, which was the reintegration of the feminine back into the masculine.

In many ways this idea is a deep reading of the biblical account of creation, because the kabbalists understood the first account of Adam having been created male and female, which assumes the technical term of the “androgynous Adam,” having read that in light of the second account of creation where the woman, the ishah, is constructed on the basis of a part of the man, ish, and that the ultimate task is for the two to be combined and restored to one flesh. So the kabbalists, reading the two stories together, understood the secret of the androgyne as ultimately relating to the female being taken from and ultimately having to be restored to the male.

This is a dominant approach in kabbalistic sources, but it is also true to say that there are aspects within these texts that already point to something of a subversion of this hierarchy, in that some texts describe the ultimate redemption as a transposition of gender, so that the female will actually rise higher than the male, or the female will sit atop of the male, or sometimes this is expressed as the female being the crown of the male. And in sefirotic symbolism, the first if the sefirot is keter and the last of the sefirot is malkhut, and when you put those terms together, you get keter malkhut, “the crown of kingship.” So you see the inversion that the first is actually subordinate to the tenth; it’s the “crown,” which is the first, of “kingship,” the tenth, so it’s the tenth that gives meaning to the first, and in that way there is an anticipation of the overturning of the hierarchy at the end of time.

Video 18 – Theosophy

The term theosophy has been used by scholars of Kabbalah to refer to medieval Jewish mysticism. The term technically means “the wisdom about God,” and it is conventionally distinguished from theology on the basis that theology is reasoned argumentation about God’s nature, whereas theosophy is a kind of illumination – a knowledge or a gnosis through the heart, or by means of the heart, into the nature of God, and the soul, and the world.

In particular in the case of the medieval kabbalists, theosophy refers most specifically to the idea that God, who is hidden in God’s essence, is revealed through ten attributes, ten middot, or sefirot, ten qualities. The kabbalists who gains knowledge of the divine through these ten attributes is said to accrue a kind of wisdom about the nature of God, which we refer to as theosophy. It should be emphasized, however, that theosophy is not a kind of abstract knowledge, but again, it is a wisdom of the heart; it is a kind of illumination, so that to know the Divine is ultimately to become one with the Divine; to become incorporated into the Name, which is the Divine essence.

Video 19 – Torah and the Divine Names in Kabbalah

One of the doctrines that is shared by a number of different mystical groups in the Jewish Middle Ages is the identification of the Torah and the Divine Name, the Tetragrammaton, yod heh vav heh, the “ineffable Name.” The idea that all of the Torah is the Name was circulated at the same time that an alternative doctrine was circulating, namely, that the Torah consists of the divine names, as is expressed by Nahmanides in his commentary on the Torah written in the 13th century.

For the Kabbalists, the idea that God’s name is the Torah was meant to communicate that all of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet are like branches that come off from the tree, whose trunk consists of the Tetragrammaton, so that the Tetragrammaton in some sense is the key word that comprises within itself the language of creation. All of reality on that count is understood by the kabbalists as an expression of that name, and that holds the key for understanding what the true nature of body or materiality consists of. Through the proper intentionality, the kabbalist has the capacity to transform the base materiality of the world into that other kind of materiality, that is the materiality that consists of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet that are comprised within the divine Name.

The association of the Name and the Torah is also important to understand the goal of the mystical path. Contemplation of the Torah, exegesis of the Torah, was understood by the kabbalists as the means by which the individual could be reincorporated into the name, to become part of the name. It is also important to understand the theurgical dimension of Kabbalah – the idea that human behavior can impact the Divine. That premise is predicated again on the identification of the Torah and the Name, and the Name consisting of the body of the Divine, the guf elohi, as some of the early kabbalists refer to it, and the body consists of limbs, so that the body of the Torah, which is the Name, consist of the commandments, the positive and the negative commandments. And the human body below, by performing the rituals, is connected to and participates in the limbs of the divine body. So this idea of the Torah and the Name really serves as the foundation for the major mystical and pietistic teachings that informed kabbalistic spirituality from the middle ages.

Video 20 – Zohar- The Book of Splendor

Zohar, which literally means “splendor,” is the major composition of kabbalistic teaching that began to emerge in the latter part of the 13th century in the geographical region known as Castile, in northern Spain. The word itself is derived from a verse in Daniel; ve-hamaskilim yazhiru ke-zohar ha-raki’ah, “The enlightened will shine like the firmament of the heaven.”

The book of the Zohar is actually not a single book, but it is an anthology, or a collection of various literary units. The earliest units comprise what is known as the midrash ha-ne’elam, “The Hidden Midrash,” and it is principally written in Hebrew, and the sayings are attributed to a number of rabbis who lived in the second century in Palestine. With the development of Zoharic literature, there began to form a clear sense of a literary fraternity consisting of ten rabbinic figures from the second and third century Palestine, and at the head of that circle or fraternity, the havraya, was Simeon ben Yohai. The major part of the Zohar was written in Aramaic, as are the latter strata of zoharic literature.

It has become increasingly clear in recent scholarship that the work itself is a very complex composition made up of these discrete parts, and the compositional and redactional history probably stretches way beyond the latter part of the 13th and early part of the 14h century, into the 16th century when the material was being prepared for publication. However we are to understand the genesis of the zoharic composition, whether it was written principally by one kabbalist, Moses de Leon, or by a circle of kabbalists, to which Moses de Leon belonged, one thing is certain; that by the latter part of the 15th century, the Zohar was emerging as the most important kabbalistic work, eventually attaining a canonical status equivalent to the Bible and the Talmud. In fact, the Bible, the Talmud and the Zohar were seen as a kind of three holy works that constitute the basic corpus of Jewish spirituality. And in time, the experiences that were described in the Zohar to Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, and his mystical colleagues, served as the blueprint for other kabbalists, and through study of the Zohar, these kabbalists were able to attain the experience that the kabbalists behind the zoharic composition had attributed to the biblical figures, and also to the rabbinic personalities, through whose voice the opinions of these kabbalists were expressed.

1 Comment on "Jewish Mysticism and Esotericism Video Transcripts"

Trackback | Comments RSS Feed

Inbound Links