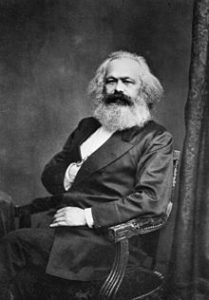

The Outbreak of the Crimean War: A Contemporary Marxist View, Karl Marx, 1854.

War has at length been declared. The Royal Message was read yesterday in both Houses of Parliament-by Lord Aberdeen in the Lords, and by Lord J.Russell in the Commons. It describes the measures about to be taken as “active steps to oppose the encroachment of Russia upon Turkey.” Tomorrow The London Gazette will publish the official notification of war, and on Friday the address in reply to the message will become the subject of the Parliamentary debate.

Simultaneously with the English declaration, Louis Napoleon communicated a similar message to his Senate and Corps Legislatif.

The declaration of war against Russia could no longer be delayed after Captain Blackwood, the bearer of the Anglo-French ultimatissimum to the Czar, returned on Saturday last with the answer that Russia would give to that paper no answer at all. The Mission of Captain Blackwood, however, has not been altogether a gratuitous one. It had afforded to Russia the month of March, that most dangerous epoch of the year to Russian arms.

The publication of the secret correspondence between the Czar and the English Government, instead of provoking a burst of public indignation against the latter, has-incredible dictubeen the signal for the Press, both weekly and daily, to congratulate England on the possession of so truly national a Ministry. I understand, however, that a meeting will be called together for the purpose of opening the eyes of a blinded British public to the real conduct of the Government. It is to be held on Thursday next in the Music Hall, Store Street, and Lord Ponsonby, Mr. Layard, Mr. Urquhart, etc., are expected to take part in the proceedings. . . .

We are informed that on the 12th inst., a treaty of triple alliance was signed between France, England, and Turkey, but that, notwithstanding the personal application of the Sultan to the Grand Mufti, the latter supported by the corps of the Ulemas, refused to issue his fetva sanctioning the stipulation about the changes in the situation of the Christians in Turkey, as being in contradiction to the precepts of the Koran. This intelligence must be looked upon as being most important, as it caused Lord Derby to make the following observation-

“I will only express my earnest anxiety that the Government will state whether there is any truth in the report that has been circulating during the last few days, that in this convention entered between England, France and Turkey, there are articles which will be of a nature to establish a protectorate on our part as objectionable at least, as that which, on the part of Russia, we have protested against.”

The Times of to-day, while declaring that the policy of the Government is directly opposed to that of Lord Derby, adds- “We should deeply regret if the bigotry of the Mufti or Ulemas succeeded in opposing any serious resistance to policy.”

In order to understand both the nature of the relations between the Turkish Government and the spiritual authorities of Turkey, and the difficulties in which the former is at present involved with respect to the question of a protectorate over the Christian subjects of the Porte, that question which ostensibly lies at the bottom of all the actual complications in the East, it is necessary to cast a retrospective glance at its past history and development.

The Koran and the Mussulman legislation emanating from it reduce the geography and ethnography of the various peoples to the simple and convenient distinction of two nations and of two countries; those of the Faithful and of the Infidels. The Infidel is “harby,” i.e., the enemy. Islamism proscribes the nation of the Infidels, constituting a state of permanent hostility between the Mussulman and the unbeliever. In that sense the corsair ships of the Berber States were the holy fleet of Islam. How, then, is the existence of Christian subjects of the Porte to be reconciled with the Koran?

“If a town,” says the Mussulman legislation, “surrenders by capitulation, and its habitants consent to become rayahs, that is, subjects of a Mussulman prince without abandoning their creed, they have to pay the kharatch (capitation tax), when they obtain a truce with the faithful, and it is not permitted any more to confiscate their estates than to take away their houses. . . .

Constantinople having surrendered by capitulation, as in like manner the greater portion of European Turkey, the Christians there enjoy the privileges of living as rayahs, under the Turkish Government. This privilege they have, exclusively by virtue of their agreeing to accept the Mussulman protection. It is, therefore, owing to this circumstance alone that the Christians submit to be governed by the Mussulmans, according to Mussulman law, that the Patriarch of Constantinople, their spiritual chief, is at the same time their political representative, and their Chief Justice. Wherever, in the Ottoman Empire, we find an agglomeration of Greek rayahs, the Archbishops and Bishops are by law members of the Municipal Councils, and, under the direction of the Patriarch, rule over the repartition of the taxes imposed upon the Greeks. The Patriarch is responsible to the Porte as to the conduct of his co-religionists. . . .

As the Koran treats all foreigners as foes, nobody will dare to present himself in a Mussulman country without having taken his precautions. The first European merchants, therefore, who risked the chances of commerce with such a people, contrived to secure themselves an exceptional treatment and privileges originally personal but afterwards extended to their whole nation. Hence the origin of capitulations. Capitulations are imperial diplomas, letters of privilege, granted by the Porte to different European nations, and authorizing their subjects to freely enter Mohammedan countries, and there to pursue in tranquility their affairs, and to practice their worship. They differ from treaties in this essential point, that they are not reciprocal acts, contradictorily debated between the contracting parties, and accepted by them on the condition of mutual advantages and concessions. On the contrary, the capitulations are one-sided concessions on the part of the Government granting them, in consequence of which they may be revoked at its pleasure. The Porte, has, indeed, at different times nullified the privileges granted to one nation by extending them to others, or repealed them altogether by refusing to continue their application. This precarious character of the capitulations made them an eternal source of dispute, of complaints on the part of Ambassadors, and of a prodigious exchange of contradictory notes and firmans revived at the commencement of every new reign.

It was from these capitulations that arose the right of a protectorate of foreign powers, not over the Christian subjects of the Porte-the rayahs-but over their co-religionists visiting Turkey, or residing there as foreigners. The first power that obtained such a protectorate was France. The capitulations between France and the Ottoman Porte made in 1535 under Suliman the Great and Francis I; in 1604 under Ahmet I and Henry IV; and in 1673 under Mustapha II and Louis XlV, were renewed, confirmed, recapitulated, and augmented in the compilation of 1740, called “ancient and recent capitulations and treaties between the Court of France and the Ottoman Porte, renewed and augmented in the year A.D. 1740 and 1153 of the Hedgra, translated (the first official translation sanctioned by the Porte) at Constantinople by M. Devel, Secretary Interpreter of the King, and his first Dragoman at the Ottoman Porte.” Art. 32 of this agreement constitutes the right of France to a protectorate over all monasteries professing the French religion, to whatever nation they may belong, and over the Frank visitors to the Holy Places.

Russia was the first power that, in 1774, inserted the capitulation, imitated after the example of France, into a treaty, the Treaty of Kainardji. Thus, in 1802, Napoleon thought fit to make the existence and maintenance of the capitulation the subject of an article of treaty, and to give it the character of synallagmatic contract. . . .

Parts of the Holy Places and of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are possessed by the Latins, the Greeks, the Armenians, the Abyssinians, the Syrians, and the Copts. Between these diverse pretendants there originated a conflict. The sovereigns of Europe, who saw in this religious quarrel a question of their respective influence in the Orient, addressed themselves in the first instance to the masters of the soil, to fanatic and greedy pashas, who abused their position. The Ottoman Porte and its agents adopting a most troublesome systeme de bascule, gave judgment in turn favorable to the Latins, Greeks, and Armenians, asking and receiving gold from all hands, and laughing at each of them. Hardly had the Turks granted a firman, acknowledging the right of the Latins to the possession of a contested place, when the Armenians presented themselves with a heavier purse, and instantly obtained a contradictory firman. The same tactics with respect to the Greeks, who knew, besides, as officially recorded in different firmans of the Porte and “hudjets” (judgments) of its agents, how to procure false and apocryphal titles. On other occasions the decision of the Sultan’s Government were frustrated by the cupidity and ill-will of the pashas and subaltern agents in Syria. Then it became necessary to resume negotiations, to appoint fresh commissaries, and to make new sacrifices of money. What the Porte formerly did from pecuniary considerations, in our days it has done from fear, with a view to obtain protection and favour. Having done justice to the reclamations of France and the Latins, it hastened to grant the same conditions to Russia and the Greeks, thus attempting to escape from a storm which it felt powerless to encounter. There is no sanctuary, no chapel, no stone of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, that has been left unturned for the purpose of constituting a quarrel between the different Christian communities.

Around the Holy Sepulchre we find an assemblage of all the various sects of Christianity, behind the religious pretensions of whom are concealed as many political and national rivalries.

Jerusalem and the Holy Places are inhabited by nations professing different religions- the Latins, the Greeks, the Armenians, Copts, Abyssinians, and Syrians. There are 2,000 Greeks, 1,000 Latins, 350 Armenians, 100 Copts, 20 Syrians, and 20 Abyssinians-3,490. In the Ottoman Empire we find 13,730,000 Greeks, 2,400,000 Armenians, and 900,000 Latins. Each of these is again sub-divided. The Greek Church, of which I treated above, the one acknowledging the Patriarch of Constantinople, essentially differs from the Greco-Russian, whose chief spiritual authority is the Czar, and from the Hellenes, for whom the King and the Synod of Athens are the chief authorities. Similarly, the Latins are sub-divided into the Roman Catholics, United Greeks, and Maronites; and the Armenians into Gregorian and Latin Armenians-the same distinction holding good with the Copts and Abyssinians. The three prevailing religious nationalities at the Holy Places are the Greeks, the Latins, and the Armenians. The Latin Church may be said to represent principally Latin races; the Greek Church, Slav, Turko-Slav, and Hellenic races; and the other Churches, Asiatic and African races.

Imagine all these conflicting peoples beleaguering the Holy Sepulchre, the battle conducted by the monks, and the ostensible object of their rivalry being a star from the grotto of Bethlehem, a tapestry, a key of a sanctuary, and altar, a shrine, a chair, a cushion-any ridiculous precedence!

In order to understand such a monastical crusade, it is indispensable to consider, firstly, the manner of their living, and secondly, the mode of their habitation. . . .

Besides their monasteries and sanctuaries, the Christian nations possess at Jerusalem small habitations or cells, annexed to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and occupied by the monks who have to watch day and night that holy abode. At certain periods these monks are relieved in their duty by their brethren. These cells have but one door, opening into the interior of the Temple, while the monk guardians receive their food from without, through some wicket. The doors of the church are closed, and guarded by Turks, who do not open them except for money, and close them according

to their caprice or cupidity.

The quarrels between Churchmen are the most venomous, said Mazarin. Now fancy these churchmen, who not only have to live upon but live in, these sanctuaries together!

To finish the picture, be it remembered that the fathers of the Latin Church, almost exclusively composed of Romans, Sardinians, Neapolitans, Spaniards, and Austrians, are all of them jealous of the -French Protectorate, and would like to substitute that of Austria, Sardinia, or Naples, the kings of the two latter countries both assuming the title of King of Jerusalem, and that the sedentary population of Jerusalem numbers about 15,300 souls, of whom 4,000 are Mussulman and 8,000 Jews. The Mussulman, forming about a fourth part of the whole, and consisting of Turks, Arabs, and Moors, are, of course, the masters in every respect, as they are in no way affected by the weakness of their Government at Constantinople. Nothing equals the misery and the suffering of the Jews at Jerusalem, inhabiting the most filthy quarter of the town, called hareth-el-yahoud, in the quarter of dirt, between the Zion and the Moriah, where their synagogues are situated-the constant objects of Mussulman oppression and intolerance, insulted by the Greeks, persecuted by the Latins, and living only upon the scanty alms transmitted by their European brethren. . . .

To make these Jews more miserable, England and Prussia appointed, in 1840, an Anglican bishop at Jerusalem, whose avowed object is their conversion. He was dreadfully thrashed in 1845, and sneered at alike by Jews, Christians and Turks. He may, in fact, be stated to have been the first and only cause of a union between all the religions at Jerusalem.

It will now be understood that the common worship of the Christians at the Holy Places resolves itself into a continuance of desperate Irish rows between the diverse sections of the faithful; that, on the other hand, these sacred rows merely conceal a profane battle, not only of nations but of races; and that the protectorate of the holy Places, which appears ridiculous to the Occident, but all important to the Orientals, is one of the phases of the Oriental question incessantly reproduced, constantly sniffled, but never solved.

-Karl Marx, New York Daily Tribune, April 15, 1854