The First Restoration, Rina Abrams, COJS.

Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E. meant a twofold crisis- not only was Jerusalem destroyed and countless Judeans forced to leave their land, but also they believed that the Divine Presence–the shekhina–departed from Jerusalem. In order to bring back the Divine Presence, the people felt compelled to rebuild the Temple and publicly recite the Torah. During the exile in Babylon, the Jews attempted to return to their laws and cultural practices. It is likely that the Jewish Bible took its final shape and became the central text of the Jewish religion during this period.

Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E. meant a twofold crisis- not only was Jerusalem destroyed and countless Judeans forced to leave their land, but also they believed that the Divine Presence–the shekhina–departed from Jerusalem. In order to bring back the Divine Presence, the people felt compelled to rebuild the Temple and publicly recite the Torah. During the exile in Babylon, the Jews attempted to return to their laws and cultural practices. It is likely that the Jewish Bible took its final shape and became the central text of the Jewish religion during this period.

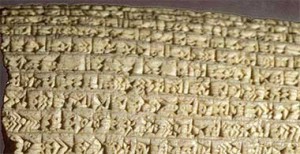

In 539 B.C.E., the armies of Cyrus, king of Persia, conquered Babylon and laid claim to the territories held by the Babylonians. The barrel-shaped cylinder of Cyrus from ca. 538 B.C.E. recorded the conquest of Babylon as well as his decree to rehabilitate desolate lands, cities, and temples. The fervent revival of religious practice by the Babylonian Jews was aided by Cyrus, who decreed that the Jews could return to Jerusalem. More specifically, he ordered that the religious institutions of the Jewish faith be strengethened. The Bible also records the decree of Cyrus in 2 Chronicles 36-22,23; Ezra 1-1-4.

The very next year (538 B.C.E.), Zerubbabel, a Jewish high priest, led 42,000 repatriates on the “First Return” to Jerusalem. Under his leadership and then under Nehemiah, a Jewish official of the Persian court, the Temple and the walls of Jerusalem were rebuilt. Ezra, a priest-scribe who led the “Second Return,” was authorized by the Persian king, Antaxerxes I, to instruct professing Jews in the laws of Moses and the observance of Jewish laws. The Bible recounts these transformations in Ezra 8.

Despite the presence of a Persian governor in Judea, the Jews enjoyed a high degree of autonomy that is demonstrated in silver coins minted in the fourth century with the inscription, “Yahud,” the Aramaic name for Judea. The right to mint coins represented the respected political status of a province. The Yehud Coins of ca. 350 B.C.E. attest to Judea’s prestige, which was due to its capital, Jerusalem, and the Temple.

Nehemiah governed Judea for approximately 12 years. When he died, internal administration passed to the hereditary High Priests, who served first under the Persians and, then, after the invasions of Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E., under Hellenistic domination.

Cyrus Cylinder – ca. 538 BCE

Tolerant King Cyrus’ Stone Decree Allows Jews to Return to Jerusalem

The conquest of Babylon by Cyrus, the King of Persia, was a turning-point in the history of the Jewish people. Cyrus’s policy of religious tolerance was manifested in the restoration of temples in Babylon and in the return of the various people exiled by the Babylonians to the countries of their origin. This was the setting for the policy of Cyrus toward the Jews, which permitted their return from Babylon and the resettlement of Jerusalem. Jews who remained in Babylon were allowed to give silver, gold, and other possessions to the House of the Lord in Jerusalem. At the head of the first wave of returning Jews was Zerubbabel, a Jewish high priest. The decree, which is recorded on the Cyrus Cylinder, permitted the exiles of Judea to return to Jerusalem. Of significant importance, Cyrus’ decree gave official status to the Temple that was to be built in the future. The reconstruction of the Temple was completed in 515 B.C.E., with financial aid from Darius I. Darius originated the custom that among the offerings in the Temple, sacrifices should be offered for the life of the king and his sons.

Yehud Coin – ca. 350 BCE

Jewish Currency Demonstrates Freedom under Persian Rule

Under the rule of the Persians from 538-332 B.C.E., the small province of Yehud (Judea) enjoyed a large degree of autonomy. The Cyrus Cylinder recorded the decree of the Persian ruler, Cyrus, that allowed for the return of the Jews to Judea and the restoration of the holy Temple. Moreover, the Persians tended not to interfere in the religious customs of their subject people. Despite the presence of an official Persian governor in Jerusalem, the High Priest became, in fact, the undisputed leader of the people of Judea.

In the fourth century B.C.E., silver coins were minted in Jerusalem, carrying the inscription “Yahud,” the Aramaic word for Judea. This right to mint coins is an indication of the great degree of autonomy granted to Judea in the last decade of Persian rule. In the Persian Empire, the right to mint coins attested to the respected political status of a province. Jerusalem’s high status to the Persians was attributable to Jerusalem being a Temple city, the capital of the province of Judea and the seat of the provincial governor who had a military force at his disposal.

See also-