The Development of Zionism in the Nineteenth Century, Based on Albright, et al, Palestine: A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

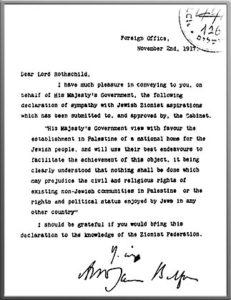

• Balfour Declaration issued by British War Cabinet on November 2, 1917. It stated that, “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

• Balfour Declaration issued by British War Cabinet on November 2, 1917. It stated that, “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 1.

• Notion of Zionism formed by several ideas –

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- For Jews, an interpretation of the messianic idea, following the resurgence of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe. (p. 1)

- A means to preserve Jewish life. (p. 1)

- Britain felt sympathy for the Jewish people, and considered the writings of the Old Testament as reason for creation of a Jewish state. (p. 1)

- Politically and geographically, Britain had imperialistic strategies, including India and extending to other near-east countries. (p. 1)

• Napoleon attempted to stake out French territory in Palestine and to halt communications between Britain and India. Took hold in Gaza and Jaffa, but was then defeated by Lord Nelson at the mouth of the Nile.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 2.

• Napoleon had promised to “restore the Jews to Jerusalem and to rebuild the Temple”, in exchange for Jewish assistance to the French. Jews paid no attention to this offer, instead allying with the Turks and thus (at the time), Great Britain. P

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947 p. 2, referencing S.W. Bacon, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, Columbia University Press, 1937, vol. II, p.329

• Many suggested a Jewish state during the 19th century including Italy, Russia and the United states, in addition to France and Britain.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 2.

• Swiss founder of the Red Cross, Henry Dunant, established the Palestine Society for international colonization for Jews in Syria and Palestine, in 1876.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 3, referencing Richard J.H. Gottheil, Zionism, Jewish Publication Society, 1914, pp. 42-43.

• Groups who favored Restoration (the returning of Jews to Palestine) were motivated by numerous beliefs-

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- That it would facilitate the arrival of the second coming. (p. 3)

- A “desire to see the Holy Land returned to its ancient beauty.” (p. 3)

- As a reward, or acknowledgement of Jewish contributions to Western society. (p. 3)

- The possibility that with a homeland, Jews would again become creative contributors to the western world. (p. 3)

• 1833, Sultan of Turkey cedes Palestine to Egypt.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 3.

• European development in the region began when Britain and its allies then defeated the Egyptian ruler of Palestine, Ibrahim Pasha, in 1840.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 3.

• Although done “on behalf” of Turkey, European and American clergy quickly established missions, schools, churches and hospitals throughout Palestine, Beirut and Syria.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 3.

• British Consulate established in Jerusalem in 1838.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 3.

• French presence heavy in region, as well. French consul is established in Jerusalem, helped renew the Latin Patriarchate in 1847 and assumed protection of the Roman Catholic Church.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 4.

• Damascus Affair, 1840.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- A Capuchin Monk, living in Damascus, disappeared. Prominent Jews in the city were arrested and charged with his murder, as prosecuted by the French Consul. Prisoner confessions were ordered to be gained through torture. (p. 4)

- British Jews organized a commission to investigate, headed by one Englishman (Sir Moses Montefiore) and one Frenchman (Adolph Cremieux). They eventually succeed in convincing Mohammed Ali of Egypt to free the prisoners. (p. 4)

- The Damascus Affair exemplified political tensions between France and Great Britain. It also united Jews world wide, strengthening the notion of Zionism. (p. 4)

• Damascus Affair focused attention on near Eastern Jews, for those living in the Western world, and saw the development of philanthropic works for the region, including schools.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 4.

• Adolph Cremieux, of the original commission sent to investigate the Damascus situation, established the Alliance Israelite Universalle, in 1860.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 4.

• Frenchman Ernest Laharanne publishes On the Oriental Question, 1848. He suggests that internationally, people should consider, “ the revival of Judea and a restoration to her of the historic function that she had exercised in ancient times.” Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 5.

• Jewish French scholar Joseph Salvador suggested a new Jewish State, “on the coast of Galilee and old Canaan,” utilizing Christian sympathies for Jews and the persecutions, as well as the idea that by its re-establishment in Palestine, a Jewish homeland might facilitate the creation of one unifying religion for all mankind. Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 5.

• British proposals for Restoration included-

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- 1845 Tranquilization of Syria and the East, by Colonel George Gawler, former South Australian Governor. He felt Jewish colonial presence in Palestine was, “the most sober and sensible remedy for the miseries of Asiatic Turkey.” (p. 5)

- 1877-1883 Edward Cazelet’s writings speak with sympathy for the tragic and extensive Jewish exile and suggested that the Jewish people possessed the ability to form a united nation for themselves. (p. 5)

- 1829-1888 Laurence Oliphant, British official in India, felt so strongly about the Christian millennial conception that he attempted, in 1882, to convince Turkey to allow the colonization of Palestine with Jews. Although Turkey refused, Oliphant himself moved to a small village in Palestine, near Jewish colonies already being established. (p. 5)

- Earl of Shaftesbury (formerly Lord Ashely) was on of Britain’s strongest supporters of Jewish restoration in Palestine. Working from a personally religious standpoint, Shaftesbury used political measures to argue his position and make his beliefs heard. (p. 6)

- In an article on Zionism, after laying out the British political advantages for trade and colonization through a Jewish state in Palestine, Shaftesbury fell back on a humanitarian point, (p. 6)

“The nationality of the Jews exists- the spirit is there and has been for 3000 years, but the external form, the crowning bond of union is still wanting. A nation must have a country.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, sighting Nahum Sokolum, History of Zionism, vol. I, pp. 206.

• Eretz Israel, as the Jews have always called the region of Palestine, is referenced in the Hebrew Bible, through Talmudic law and legend and can be found in medieval writings.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 7.

• Talmudic sayings include, “It is better to dwell in the deserts of Palestine than in places abroad” and “The merit of residence in Palestine equals that of the fulfillment of all the Commandments of Divine Law,” and “If thou wouldst behold the Divine Presence in this life – go and study the Torah in Palestine.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 7.

•

All Jewish religious services, whether observed in the home or in a synagogue, contain some mention or allusion to the rebuilding of Zion, as restoration of Israel.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 7.

• Three ideas that recur with some frequency in such services include-

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- The political notion of reviving the House of David as governance over Israel. (p. 7)

- The religious idea that with the exodus of the people of Israel, the Divine Presence had also been exiled and such restoration could only take place with the people’s return (p. 7)

- The humanitarian plea translated as, “May the All Merciful break the yoke from off our neck, and lead us upright to our land.” (p. 7)

- The messianic idea of a harmonious time of justice and peace, once the people of Israel have returned to the land of Israel. (p. 7)

• Zionism incorporated many thought trends of the 19th century, including naturalism, nationalism and social liberalism.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• “Back to the land”, a phrase used by Zionists to mean a return to the cultivation of the soil.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• Social Zionists stressed the term “productivization”, referring to occupations requiring manual labor.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• Nationalistic beliefs in the 19th century felt each national group should have their own land, but did not consider the development of a Jewish state as necessary; rather, it assumed that the Jews would assimilate in the group of the larger nation state, of which they were already a part.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• Zionists revised this take on nationalism, to encourage the possibilities of Jewish statehood.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• 1897 – First Zionist Congress at Basle organized by Theodor Herzl.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 8.

• Development of Zionist concepts and early organizational activity began in early 1880’s, concurrent with the rise of nationalism spreading through Europe.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 9, sighting S.L. Citron, Toledot Hibbet Zion (History of the Lovers of Zion Movement), Odessa, 1914, p. 9.

• Hirsch Kalischer, considered the first organizer of Zionist activity

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- Orthodox, yet liberal Prussian Rabbi, in the town of Thorn. (p. 9)

- Motivated by heavy nationalism in Italy, Poland and Hungary. (p. 9)

- His first hurdle to overcome was the notion that Jews would/could only be restored to Palestine after the coming of the Messiah, via supernatural forces and to replace that with the idea that in fact redemption could come through “self-help”, making way for the Messiah. (p. 9)

- Through correspondence with other leading rabbis of his time and various publications, Kalischer also promoted the idea that Jewish colonization of Palestine would promote agricultural development, through the tilling of the soil. (p. 9)

- Successfully influenced Cremieux’s Alliance Israelite Universalle to also establish an agricultural school outside of Jaffa called Mikven Israel (the in-gathering of Israel), in 1870. This was the first Jewish agricultural settlement in Palestine. (p. 9)

• Moses Hess, Zionist theorist, author of Rome and Jerusalem; The Latest National Question (1862).

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- Was roused into the Jewish political arena by the Damascus Affair of 1840, and the European response to it. (p. 10)

- Nicknamed “Communist Rabbi Moses”, as a non-Marxist follower of “true socialism”.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 9, sighting Sidney Hook, From Hegel to Marx, Reynal and Hitchcock, 1936, p. 188.

• When Frederick William IV of Prussia, wanted to segregate Jews as a separate community, independent of certain rights and responsibilities, Jewish leaders responded with an insistence on a religious identity only, and that they should not constitute a separate nation; they were Germans, first and foremost.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 10.

• This “equal rights” movement on the part of the Jews saw the birth of Reform Judaism, assimilation to mainstream culture. References to a return to Zion were eliminated from prayer books and traditional Jewish practices were reformed to appear more Protestant.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 10.

• Hess’s emphasis on the line between family and nation came from his philosophy and interpretation of Judaism. A theme in many of his writings, Hess believed,

“Judaism has never drawn any line of separation between the individual and the family, the family and the nation, the nation and humanity as a whole, humanity and the cosmos, nor between creation and The Creator. Judaism has no other dogma than the teaching of the unity.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 11, sighting Moses Hess, Rome and Jerusalem; The Latest National Question (translated by Meyer Waxman), Bloch, 1943, p. 84.

• Hess encouraged a “renascence” of Jewish national consciousness, as opposed to the minimalization and assimilation being seen.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 11.

• Hess believed that like all nationalities, Jews had their own contributions to make for the development and improvement of humanity, contributions which may not be developed or fostered through self-obliteration, or the denial of a Jewish nation.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 11.

• Hess understood that the first step was to legalize and legitimize the resettlement in Palestine. His argument for social justice was,

“The acquisition of common ancestral soil, the organization of the work on a legal basis, the founding of Jewish societies of agriculture, industry and commerce on the Mosaic (i.e. social principles) – these are the foundations on which Oriental Jewry will rise again and in its rise will kindle the glowing fire of the old Jewish patriotism and light the way to a new life for the Jewry of the entire world.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947. p. 12.

• Hess not only frowned upon the German Jews’ attempt to completely assimilate, he also perceived it would never take hold. Hess noted in his writings that the differences Germans viewed between themselves and Jews were not based in religious identity, but rather racial, or ethnic properties. Hess hoped that as German Jews came to this realization, they might redirect their efforts towards a “political regeneration of their people”, rather than fighting for emancipation from it.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 12.

• During the 19th century, Eastern European social conditions were quite different from those in Western Europe. Although assimilation was the preferred doctrine of the “intelligentsia”, Jewish communities in the east were large and self-contained, with their own schools (Heder and Yisheva) and the traditional way of dress.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 13.

• The scholars and educated people spread encouragement towards assimilation throughout these Jewish communities in the Hebrew language.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 13.

• Haskalah, or the Jewish enlightenment movement, saw a revival of the Hebrew language throughout these communities as a positive return to unique Jewish cultural aspects.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 13.

• Perez Smolenskin, born 1842 in Mogivel, Ukraine. Credited with shifting the Haskalah (enlightenment) movement into the Hatehiah, or renascence.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 13.

• Smolenskin maintained three elements to his philosophy-

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

1.) Maintenance of and emphasis on fundamental religious traditions, as embraced by the majority Jewish population.

2.) Bringing back Hebrew as the dominant language for Jewish literature and prayer (no longer solely for the educated/scholarly).

3.) A stated attachment to Palestine.

• Leo Pinsker, born 1821 in Tomashov, Poland. Considered the Father of Russian Zionism and perhaps, “The most important figure in the development of the Zionist movement before Theodor Herzl.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

• Pinsker was originally opposed to the “emancipation” and return to Jewish cultural traditions such as Hebrew literature, Jewish thought and notions of a return to Palestine.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

• In opposition to his younger contemporary, Perez Smolenskin, Pinsker initially believed tin the Russification of the Jews.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

• Pinsker changed his position dramatically, following the Russian pogroms of 1881 and the May Laws of 1882, which confined Jewish communities to Pale.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

• His first pamphlet was published soon after these events, anonymously, with the title Auto-Emancipation- An Admonition to His Brethren by a Russian Jew. He urged Jews to emancipate themselves by re-establishing themselves as a nation, in territory of their own. His pamphlet concluded with the statement, “Help yourself and God will help you!”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 14.

• Pinsker’s writings reflect an early ideation of anti-Semitism. Recognizing that the Diaspora had displaced Jews in a way that made them constant “guests” or visitors in host countries, and that they would eventually overstay their welcome, never being able to truly and fully assimilate while retaining self-respect and a Jewish identity.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 15,

• From Pinsker’s pamphlet Auto-Emancipation-

“Though you prove yourself patriots a thousand times, you will still be reminded at every opportunity of your Semitic descent. This fateful momento hori will not prevent you, however, from accepting the extended hospitality, until some fine morning you find yourself crossing the border and you are reminded by the mob that you are, after all, nothing but vagrants and parasites, without the protection of the law.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 15, quoting Leo Pinsker, Auto-Emancipation, Maccabean Publishing Company, New York, 1906, p. 5.

• Pinsker felt the only viable solution was a re-creation of a Jewish nation, where Jews could govern themselves and live within their own laws, use their own language, etc… In the beginning, he was not partial to Palestine; Pinsker also considered the United States as an option.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 16.

• In 1884, Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) met in Upper Silesia, to address the needs of a Jewish homeland and to raise funds for Jewish colonies settling in Palestine. Leo Pinsker was elected president.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 17.

• Leo Pinsker established “The Society for the Support of Jewish Agriculture in Syria and Palestine”, better known as the Odessa Committee, which would later become part of the World Zionist Organization.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 17.

• Zionist settlements begin in Palestine in 1882.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 17.

• Bilu, a group of approximately 500 young people determined to pioneer the settlements in Palestine. Established in Kharkov in 1882, in response to the pogroms.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 17.

• Bilu took their name from a biblical verse in Isaiah translated as, “And they shall bet their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war no more.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 17.

• Asher Ginsberg, pen name of Ahad Ha’am, born 1856 in Kiev. Originator of Spiritual Zionism.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 18.

• Ha’am was greatly influenced by European thinkers of the time including Locke, Hume, Comte and Pisarev.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 18.

• Spiritual Zionism stems from the belief that Israel is a nationality, including more than just religion but also ethics and law, mysticism and poetry with an emphasis on ethics.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 19.

• From this ideology came the notion that one could be a “good Jew” without being overly religious.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 19.

• Ahad Ha’am was clear in his views that Zionism would not eliminate anti-Semitism, nor would it solve the many financial problems of the Jews. He recognized the development of a state in Palestine would require hard work, commitment and sacrifice.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 20.

• Albright, et al, summarize Ha’am’s Zionist views in the following manner-

“Zionism should aim to resolve not the problem of the Jews as individuals, but the problem of the Jews as an historical national culture” and, “Zionism [has] a moral objective – the emancipation of the Jews from the inner slavery and the spiritual degradation which assimilation had produced, and the creation of a sense of national unity and a life of dignity and freedom.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 20.

• The utilization of Hebrew as the formal and unifying language for the Jewish people became paramount, again, towards the “revival of the spirit” for Jews.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 20.

• Ahad Ha’am was openly critical of the work being done by Hovevei Zion and philanthropic contributors such as the Baron de Rothschild.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 21.

• Ahad Ha’am was the first to point out and discuss the issue of the Arab occupants in Palestine. Although he acknowledged that in many ways the Jewish colonies were being well received, paying good prices for the land they purchased and paying strong wages for Arab labor, he also pointed out that if at some point these people became disenchanted or felt threatened by the settlers, they could well become a danger.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 21.

• Ha’am’s vision of Palestine as a spiritual Zion for Jews worldwide is clearly reflected in this excerpt from a correspondence he sent to Dr. Pinsker in 1892-

“So that every Jew in the Diaspora will think it a privilege to behold just once the center of Judaism, and when he returns home will say to his friends, ‘If you wish to see the genuine type of Jew, whether it be a rabbi or scholar or a writer, a farmer or an artist or a businessman – then go to Palestine and you will see it.’”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 21, quoting from Leo Pinsker, Auto-Emancipation, Maccabean Publishing Company, New York, 1906, pp. 154-155.

• Labor movements were a small but important factor in the physical development of Palestine via the Zionist vision/concept. Labor groups began to associate themselves with and work for the Zionist movement near the beginning of the 20th centuty.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 22.

• Many other forms of socialist ideals contemplated Zionism. Some Jewish socialist groups felt complete socialist assimilation would solve problems of alienation and discrimination by making everyone “equal”. Others considered cultural Zionism of the Jewish Diaspora a sufficient response, incorporating Yiddish as the binding language and basis of nationality.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 22, sighting Oscar I. Janowsky, The Jews and Minority Rights, chapters 1 and 2.

• Nachman Syrkin, born 1868 in Mogilev, Russia. Influenced by Hovevei Zion.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947.

- Argued against assimilation notions (p. 23)

- Rebuked the removal of all mentions of the messianic idea by the Reform movement, sighting it as a “loss in moral force”. (p. 23)

- Understood that true socialism, in a pure form could in fact solve many problems of Jews in the Diaspora, as it could equalize rights and entitlements for all oppressed people, but also noted the political and social conditions unique to the Jewish people that would require more than socialism for true resolution. (p. 23)

• “Zionism arose out of the inferior social position of the Jews and in their lack of power.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 24

• Zionism also built on traditional Jewish notions (both spiritual and cultural) of social justice, as a solution for all Jews regardless of, or perhaps even in spite of, class.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 24.

• Quoting Syrkin,

“Zionism must fuse with socialism in order to become the ideal of the entire Jewish people, of the proletariat, of the middle class, of the intelligentsia, as well as of the idealistic.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 24.

• Ber Borochov, born 1881 in Ukraine. Family moved almost immediately, due to pogroms of 1881 and 1882.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 24.

- Also influenced by Zionism (Hovevei Zion) and socialism early on. (p. 24)

- Expelled from Russia in 1916 for revolutionary activities. (p. 24)

- Agreed with Syrkin on idea of Zionism, but developed a synthesized Marxist view in his approach. (p. 24)

1.) Emphasized importance of nationality in a social organization.

2.) Equally emphasized class structure.

- “Borochov believed that nationality arose out of common conditions of production as much as out of common tradition and common territory.” (p. 24)

- Borochov identified the main source of the Jewish problem as their labor positions, distant from influential branches of production. (p. 25)

Said Borochov, “The concentration of Jewish labor in any occupation varies directly with the remoteness of that occupation from the soil” and that the Jews were too far displaced from “the most important, most influential and the most stable branches of production, far removed from the occupations which are at the hub of history.”

Ber Borochov, Nationalism and the Class Struggle, New York, 1937, pp. 68-69, as sighted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 25.

• Borochov noted that the development of capitalism was also having an adverse affect within Jewish communities, pitting Jewish capitalists against Jewish workers and increasing tensions between “native” workers and “alien” (Jewish) workers.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 25.

• Theodor Herzl born in 1860 in Pesth, Hungary. Considered the founder of Political Zionism.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 25.

- Published Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in 1896 and dismissed the idea of Zionism as a solution for the Jewish problem. (p. 26)

- Although originally not keenly aware of the thoughts and writings of his predecessors such as Pinsker, his views reflected much of the same sentiments, including the political need for a Jewish state. (p. 26)

- He was set apart however, by his intensity and zeal for the Zionist idea and his advocacy for a worldwide organization of Jews. (p. 26)

• Albright, et al, also comment on Herzl’s dynamic personality and physical presentation.

“In his meticulous dress and manner, he was the perfect European; his dark coloring and deep set eyes gave a Semitic cast to his countenance and his erect stature and full black beard were reminiscent of an ancient Assyrian prince. From youth, he was marked for leadership.” (p. 26)

• Exodus was one of Theodor Herzl’s favorite stories from the Bible.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 27.

• Herzl was extremely interested in scientific and technological development and advancement, but not so much for the pure knowledge of it as more for the potential these fields held for the improvement of human life and society.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 27.

• When Herzl was 22, he became more aware of , and thus concerned with, the socio-political issues facing middle class Jews.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 27.

• Herzl noted that “invisible ghettos” remained in tact even after Hungary’s emancipation of their Jews in 1867, with Jewish people still being thought of as different and separate and choosing to move within their own communities. He called this the “compulsion of the ghetto.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 27.

• In these early days, Herzl’s solution was not unlike that of many of his liberal contemporaries; merge and integrate the Jewish population, via intermarriage and complete assimilation.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28.

• Immediately after committing these thoughts to his diary, (literally the following day) Herzl read Eugene Duhring’s book, The Jewish Problem as a Problem of Race, Morals and Culture (1881), in which the author claimed that Jews were “fundamentally” and racially inferior.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28.

• Duhring’s book went on to state that because of their compromised race and abilities, Jews should be forced “back to their ghetto”, live under special laws and restrictions and removed entirely from the arenas of the theatre and the press, with limitations on public service.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28.

• Herzl’s reaction to this writing was noted in the following diary excerpt,

“An infamous book… If Duhring who unites so much undeniable intelligence with so much universality of knowledge, can write a book like this, what are we to expect from the ignorant masses?”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28 quoting from Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940.

• Herzl resigned from his school fraternity shortly thereafter, when the group of young men participated in a supportive demonstration for Richard Wagner following an anti-Semitic speech.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28.

• During the 1880’s, Herzl studied and practiced law in Vienna for a period, but also developed his taste for writing, through comic plays that were produced around the western world.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 28.

• Herzl joined the very distinguished, very liberal newspaper Wiener Neue Freie Presse, and in 1891 was sent to live and work as a correspondent in Paris.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 29.

• Anti-Semitic publications were on the rise in France, as well, including Edward Drumont’s book, La France Juive (1885) and the anti-Semitic paper that followed, La Libre Parole.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 29.

• Theodor Herzl conceived extreme and impractical responses to anti-Semitism during these first years in Paris, including-

- Jews should engage in duels with those who insult or disrespect them. If the Jew wins, his honor is maintained and if he loses (dies) it would be seen as an “unjust sacrifice”.

- Older Jews should escort Jewish youth to the Catholic churches for the purpose of mass baptisms (towards assimilation).

- Establish a newspaper that would counter anti-Semitism, but be staffed exclusively with non-Jews.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 29

• Albright, et al, note that although fantastical, Herzl’s ideas belied notions that would later be seen in his “mature” Zionist ideas, including that the issues for the Jewish people must be of public concern, that Jews and non-Jews alike must acknowledge and address anti-Semitism as a problem, and that there must be a solution both definitive and broad in scope.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 29

• The Dreyfus Trial was the final turning point for Theodor Herzl. It represented the complete failure of emancipation/assimilation theory in it’s purest form, for Alfred Dreyfus, a decorated military career man who had completely separated himself from the ghetto and his Jewish heritage, was humiliated and subjected to shouts from fellow Frenchmen, “A mort! A mort les Juifs!” as his decorations were ripped from his jacket.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 30.

• Reflecting upon the incident four years later, Herzl wrote,

“The Dreyfus case embodies more than just a judicial error; it embodies the desire of a vast majority of the French to condemn a Jew and to condemn all Jews in this one Jew… In republican, modern, civilized France, a hundred years after the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the French people, or rather the greater part of the French people, does not want to extend the rights of man to Jews. The edict of the great revolution has been revoked.”

Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940, pp. 115-116 as quoted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 30.

• As Herzl developed his conception for a Jewish state, he wrote,

“Throughout the two thousand years of our dispersion we have lacked unified political leadership. I consider this our greatest misfortune. It has done more harm than all the persecutions. It is this that is responsible for our inner decay.”

Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940, pp. 127 as quoted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 31.

• Theodor Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) – A background

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 31-32.

- Original working title in early 1895 was Address to the Rothschilds, as he hoped his notes would sway philanthropic means for his ideas, from the wealthy Jewish banking family. (p. 31)

- In the fall of 1895, Herzl was invited to speak at the Maccabeans, a club for prominent English Jews. Herzl and his ideas were well received and his audience encouraged him to consider Palestine as the only true location for a Jewish homeland. (p. 31)

- Upon returning to Vienna in November 1895, Herzl revised both the title and some content of his writings. It was published in 1896 in Vienna, with the title Der Judenstaat. (p. 32)

• The following summarizes Herzl’s revised work and ideas, through direct quotes from Der Judenstaat as well as an overview of his theories and philosophies supporting his publication.

“The Jewish question exists. It would be stupid to deny it… The Jewish question exists wheresoever Jews are to be found in large numbers… I consider the Jewish question to be neither social nor religious even though it takes on these and other colorations. It is a national question, and in order to solve it we must… transform it into a political world question…”

Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940, pp. 160-161 as sighted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 32.

“The distinctive nationality of the Jews neither can, nor must be destroyed. It cannot be destroyed because external enemies consolidate it. It will not be destroyed; this is shown during two thousand years of appalling suffering. It must not be destroyed, and that, as successor to numberless Jews who refused to despair, I am trying once more to prove in this pamphlet.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 33, quoting a revised translation of Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (translated by Sylvia d’Arigdor), 1934, p. 18.

- Herzl considered two viable locations for the Jewish state, both Argentina for its good weather, fertile soil and relatively few inhabitants, as well as Palestine for its historic importance.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 34.

- Herzl was intent on receiving political assurance and support for the immigration of Jews to either land, so that the process would not be halted or impeded later by reactions of the native people.

“An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues until the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened and forces the government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless based on an assured supremacy.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 34, quoting a revised translation of Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (translated by Sylvia d’Arigdor), 1934, p. 28.

- Herzl envisioned a large and continual immigration of Jews to the new state, over many generations. His logic was to first send laborers and agricultural settlers, to build roads, cultivate soil, construct houses and develop waterways. This would facilitate trade, which would develop markets and thus entice more immigrants.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 34.

- Herzl envisioned a seven-hour workday.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 35

- Herzl rejected theocracy as government for the state, keeping religion important but separate from politics.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 34.

- Herzl projected the Jewish state would not require more than a minimal army, as it would remain neutral.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 35.

- Herzl suggested a flag of white (for a new beginning) with seven gold stars (for the seven hour work day).

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 35.

- Herzl rejected both Hebrew and Yiddish as “national” languages, feeling that instead each group should bring their native tongue and whichever proved to be the most utilitarian would be selected.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 35.

Reactions to Der Judenstaat were mixed.

- The Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums, a popular German-Jewish newspaper felt that the very religious, or orthodox Jews should not encourage or act towards the development of a Jewish state until, “the visible signs of God’s direct intervention” were known.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 35.

- Hovevei Zion members were unsettled by Herzl’s failure to acknowledge, or build on, previous ideas for such a movement and that he was not partial to either the Hebrew language or the location of Palestine.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 36.

- Kaddimah (Eastward), a group of young Viennese student Zionists embraced Herzl and his vision.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 36.

- Businessmen, writers, rabbis – thousands of Jews from across the Jewish world wrote letters of support to Herzl, for his exciting vision and new approach.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 37.

- Ritter Von Nevlinksi, a Polish nobleman, was drawn to Herzl and his wild ideas, as much out of curiosity as was his interest in and ties to Russian/Turkish/Balkan politics.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 37.

• With his ties to the Sultan of Turkey, through Ritter Von Nevlinski, Herzl conceived of a plan wherein the wealthy Jews of the world might raise enough money to pay off Turkey’s national debt and in exchange, Turkey would give Palestine to the Jews. Herzl did not get a meeting directly with the Sultan and his plan was not accepted as he had hoped; however, it was agreed that perhaps Turkey would allow a “vassal state” in Palestine, allowing mass Jewish immigration and self-governance (in exchange for debt repayment).

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 37.

• Not discouraged, Herzl took the Sultan’s offer to England, where he met with little support and a great number of barriers, several of which would require a great deal of dependence on philanthropic sources as opposed to those who would contribute financially to his vision, one day becoming a physical part of it.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 38.

In fact, Baron de Rothschild refused support, even when Herzl did eventually meet with him. The Baron felt a large immigration to Palestine could compromise the entire colonial effort in the region, attracting hostile attention.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 39.

• Still, Herzl received great support from the public at large and working with the idea of a “Zionist Congress”, as suggested by Nathan Birnbaum (one of the founders of Kaddimah), Herzl developed a broader concept of a “World Congress of Zionists”.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 39

• Herzl used the written word this time to rebuke his adversaries, discounting notions that Zionism was at all similar to Christian missionary movements (wherein Christian goals were to convert people).

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 39.

• Herzl labeled anti-Zionist rabbis as “Protest Rabbis”, a name which has since been used to refer to “rabbinical opponents of Zionism”.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 39

• On the activist front, Herzl worked to engage Jews truly committed to his vision of Zion (as opposed to philanthropists who only wanted to donate money and then make demands from a distance).

“The Jewish question must be taken away from the control of the benevolent individual. There must be created a forum before which everyone acting for the Jewish people must appear, and to which he must be responsible.”

Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940, p. 218 as sighted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 40.

• 1897 – The first Zionist Congress met in Basle. It was attended by 197 elected representatives from the United States, Palestine and Europe and represented all aspects of thought on Zionism.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 40.

Herzl facilitated the session, outlining the goals and objectives for the meeting. They included-

1.) Jews must help themselves, independent of supernatural or other external powers.

2.) Colonization should be well planned, well organized and large in scale.

3.) Everything should be done openly, honestly and with general public approval.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 40.

• Herzl’s opening was followed by Max Nordau who addressed, “The Condition of Jewry at the Close of the Nineteenth Century.” The Zionist mission statement was based on key points from his speech, including-

1.) “The aim of Zionism is to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by

public law.”

2.) Palestine would be colonized with Jewish farmers/ land workers and industrialists.

3.) Work in a manner that would bring individual Jews together with their current country’s government, and work within a legally acceptable frame to meet the Zionist goals.

4.) Strengthen identity through national pride and consciousness

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 41.

• Everyone (including Theodor Herzl) was in agreement on the location of Palestine for the Jewish state.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 42.

• The congress then developed committees, agreed to meet annually, and was determined, “the chief organ of the Zionist movement”.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 42.

• Theodor Herzl was elected President of the Zionist Congress and Max Nordau was Vice President.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 42.

• David Wolffsohn developed the national flag, white with two wide, blue stripes and in the center as Shield of David. Albright, et al, note that it “resembled a talith, or Jewish prayer shall.”

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 42.

• Naphtali Herz Imber composed the song Hatikvah (The Hope) and as it was sung periodically throughout meetings of the Congress, it became the Jewish national hymn.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 42.

• Herzl continued to struggle politically, attempting to find support for the approval of and protection for mass Jewish immigration to Palestine and Syria.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 43.

• Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany was initially supportive of a Chartered Land Development Company that would be managed by a German protectorate, but his support came largely from anti-Semitic feelings – He saw it as a means to remove Jews from Germany.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 43.

• Kaiser Wilhelm II would later withdraw his support, when it became evident that Turkey’s Sultan was opposed to the idea and that it could be seen as an attempt by Germany to exert “influence over Turkish territory”.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 44 sighting Alex Bein, Theodor Herzl, A Biography (translated from German by Maurice Samuel), Philadelphia, 1940, pp. 308-309.

• By the time the fifth Zionist Congress convened in 1902, there was quite a bit of internal opposition to Herzl and his methods, particularly from members of Hovevei Zion groups and even the Russian Zionists.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 45.

• Ahad Ha’am’s ideas were instrumental in forming the first official opposition group within the Congress, calling themselves the “Democratic Zionist Faction”. They emphasized-

- Cultural Zionism

- Nationalism strongly rooted in culture

- More democracy in the movement’s leadership

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 45.

• In 1902, Herzl published Altneuland. It outlined a utopian future for Palestine through Zionist development, with an emphasis on science and technology. Part of his vision included-

- The irrigation of dry areas

- Draining of swamps

- The elevation drop between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan Valley could be utilized to generate hydroelectricity.

- Health and social services of the highest quality would be provided

- Women would have equality with men in all ways

- No race laws

- Arabs would live side by side in peace with their Jewish neighbors

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 46.

• This view met with great criticism from Ahad Ha’am. He felt it was too highly romanticized and fantastical and said its sentimentality was “the work of a dilettante”. Ha’am’s main criticism was that Herzl’s projected vision was too generic. “It lacked Jewish character” and made no mention of the Hebrew language and literature.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 47.

• Additional opposition came from within the Congress and from the orthodox representatives. Although they agreed on subjects of political and practical policy work towards Zionism, they did not support emphasis on educational movements, as they worried the importance of religious study would be lost.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 47.

• Dr. Chaim Weizmann, developed concept of Organic Zionism.

- Member of “democratic fraction” within Congress

- Addressed his group at their first meeting in 1901

- Agreed with Ha’am on many points, but also appreciated Herzl’s contributions and zeal.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947. pp. 47-48.

• Chaim Weizmann’s views included-

- A positive attitude by the Zionist organization regarding the “economic amelioration” of the Jews.

- The importance of Hebrew cultural work as a steadfast element of Zionist work.

- Suggested a Hebrew University in Jerusalem

- Also felt strongly about the actual work of the colonization of Palestine

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, pp. 47-48.

• Weizmann’s concept of Organic Zionism was a vision for balance between the practical, the cultural and the political needs.

Joseph Klausser, Dr. Weizmann, His First Period of Activity, Hadoar (Hebrew), February 16, 1945 as sighted in Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 48.

• In 1903 at the sixth Zionist Congress, Herzl suggested a British proposal for a Jewish state in Uganda. He acknowledged it would only be a temporary home, until Palestine was more accessible, but was responding to the worsening conditions of the Jews in Eastern Europe at the time.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 48

• A commission was sent to explore the proposed region and returned in 1905 with the report that the area was unsuitable for any large agricultural population.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 49.

• Theodor Herzl died at the age of 44 in July of 1904, apparently “worn out by his exertions and by the internal conflicts [of the Zionist Congress].

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 49.

• With Herzl gone and Uganda no longer a consideration, the Zionist Congress split and divided into more fractions, once again.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, pp. 49-51.

- The “politicals” followed in Herzl’s footsteps, seeking political backing and guarantees before launching any large-scale practical development. (p. 49)

- The “practicals” believed the first task should be to get as much colonization and development going as possible, and that from this would come unity and strength for the Zionist political position. (p. 49)

- Zionist Socialists established themselves as a defined group within the Congress in the early 1900’s. (p. 51)

- The Mizrahi formed in order to represent the religious standpoint. (p. 51)

• At the time the First World War broke out, the Jewish settlements in Palestine (Yishuv) were developing quickly. These settlements had begun in the mid 1800s, with immigrants financially supported from money (Halukah) distributed by Jewish collectives in their native countries.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 51.

• Schools for both education and vocational training were rapidly being built, with the Alliance Israelite Universelle (established 1860) expanding, and new schools like Hilfsverein der Deutschen Juden being established. Funding for schools in Palestine came from western Jewish philanthropic sources.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 51.

• The three most significant agricultural developments in the 19th century were-

1.) Mikvah Israel, an agricultural school outside Jaffa, supported by the Alliance Israelite Universelle (1870)

2.) Petach Tikvah (the Door of Hope), the development of a stretch of land just north of Jaffa in 1878.

3.) Rishon le-Zion (the First Zion) settled by young Russian Zionists from Bilu in 1882.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947. p. 52.

• Hebrew became the national language in the early 20th century simply out of necessity. As Jews from around the world immigrated to the numerous settlements, they brought their native languages including Arabic, Persian, Ladino, Yiddish, French, English and German. Hebrew was the only language they all had in common.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 53.

• Eliezer Ben Yehuda, born 1858 in the province of Vilna. Settled in Palestine in 1882 and spent his life reviving the Hebrew language.

- Developed the Modern Hebrew Thesaurus

- Advocated for Hebrew as the language for public schools.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 53.

• The Zionist movement and its resulting settlements in Palestine stimulated growth and immigration to Palestine, beginning in the late 1800s.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 54.

• The pogroms of 1903 and worsening social conditions for Jews in Eastern Europe also spawned more immigration.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 54.

• By 1914 there were approximately 90,000 Jewish inhabitants in Palestine and nearly 12,000 of them resided in Jewish agricultural settlements.

Albright, et al, Palestine- A Study of Jewish, Arab and British Policies, vol. 1, Yale University Press, 1947, p. 54.